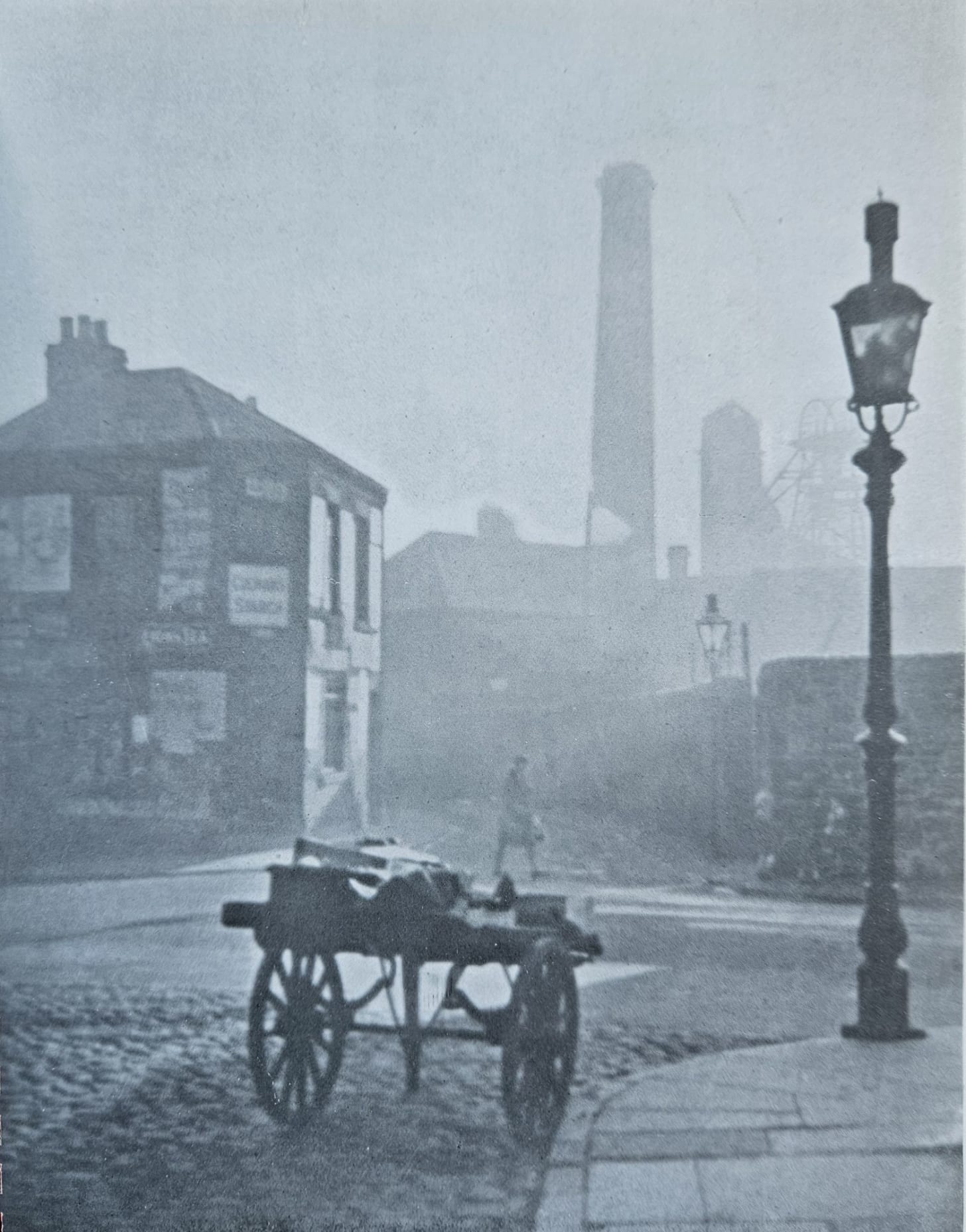

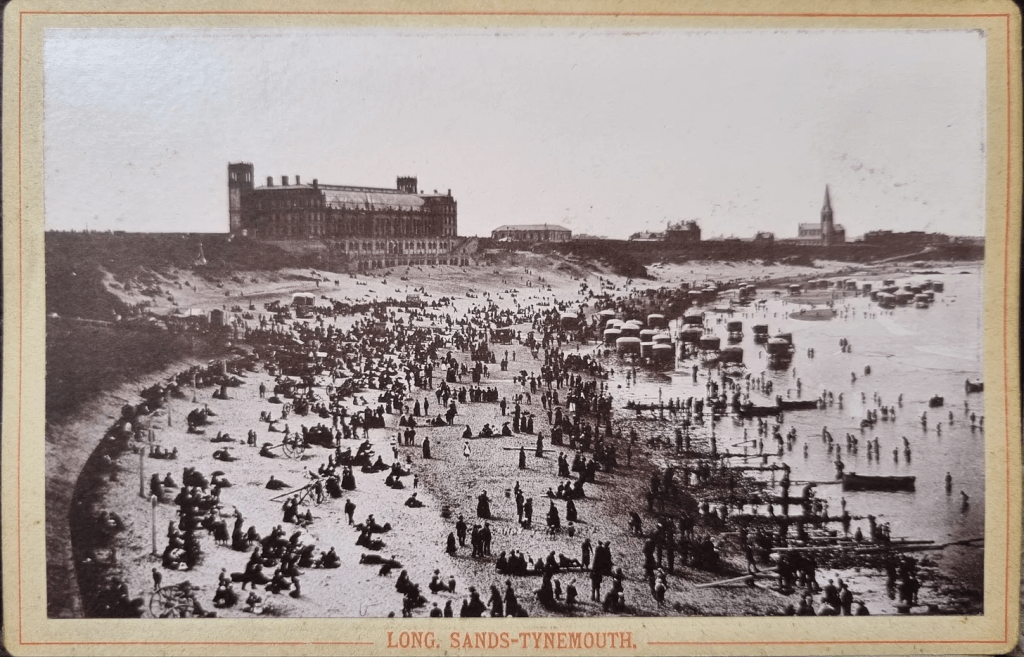

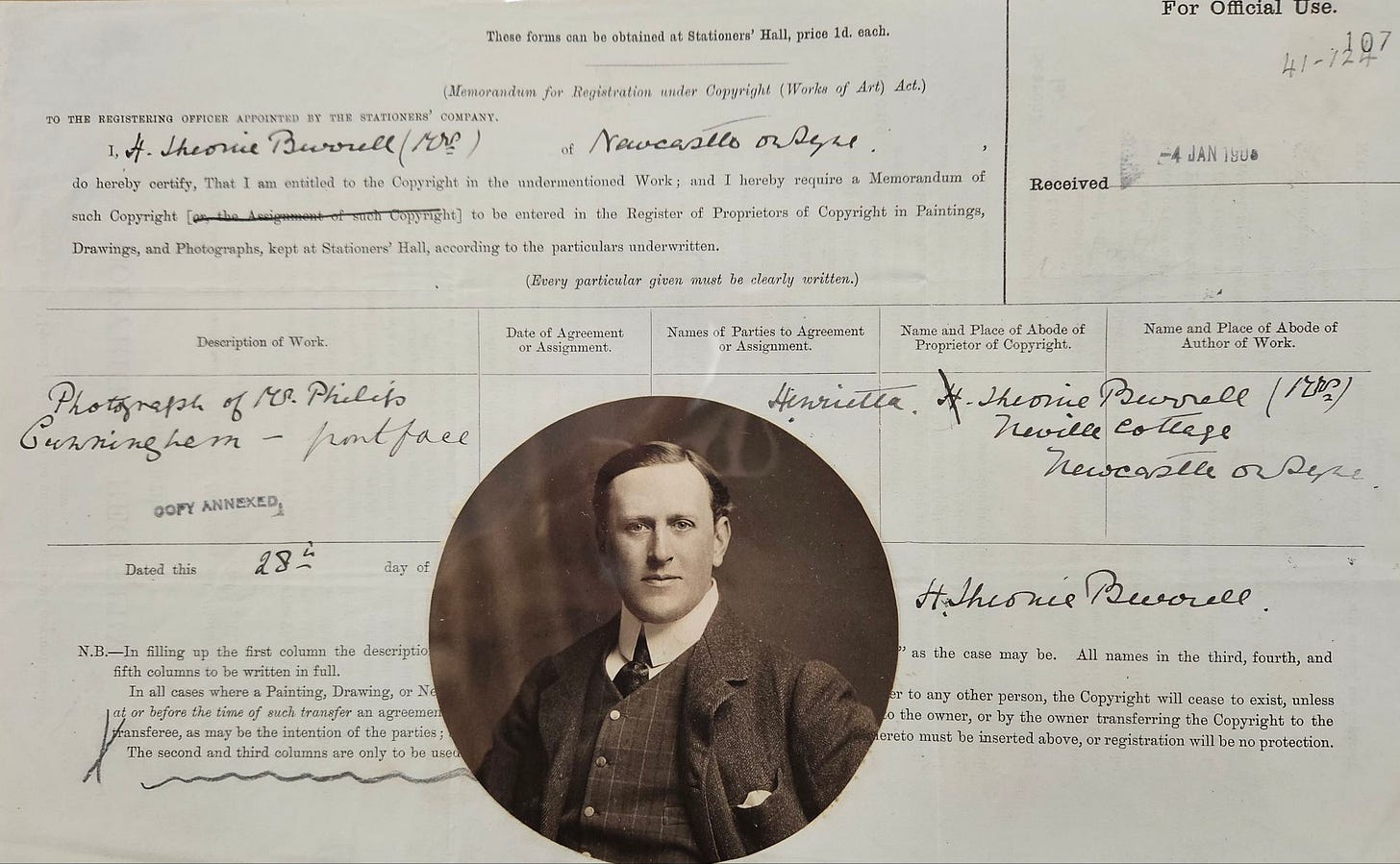

The town of South Shields in North East England was a hotbed of photography from the medium’s earliest days.

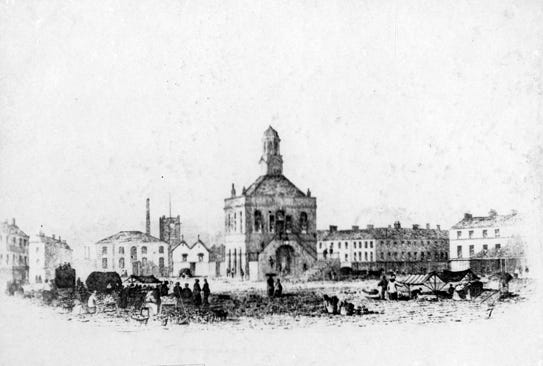

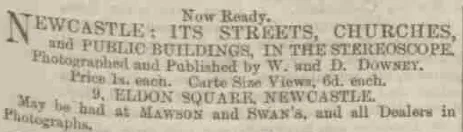

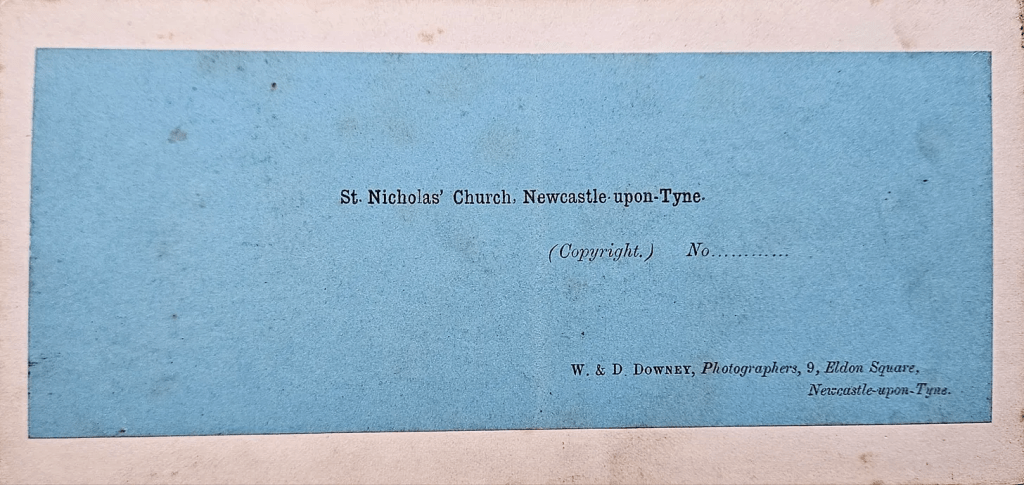

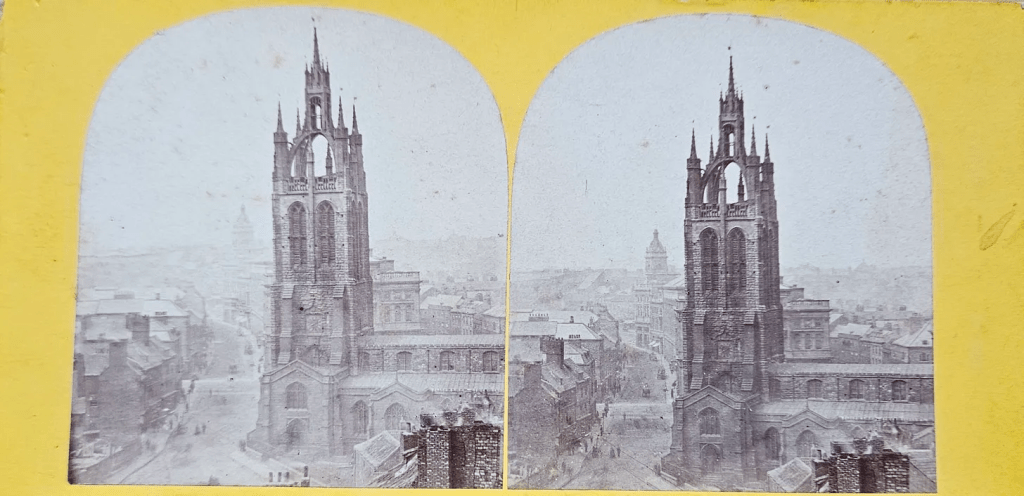

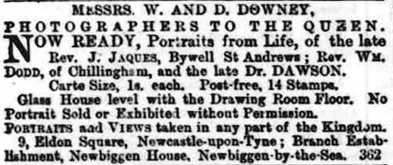

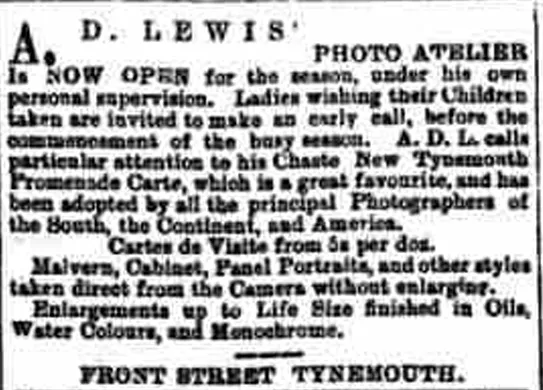

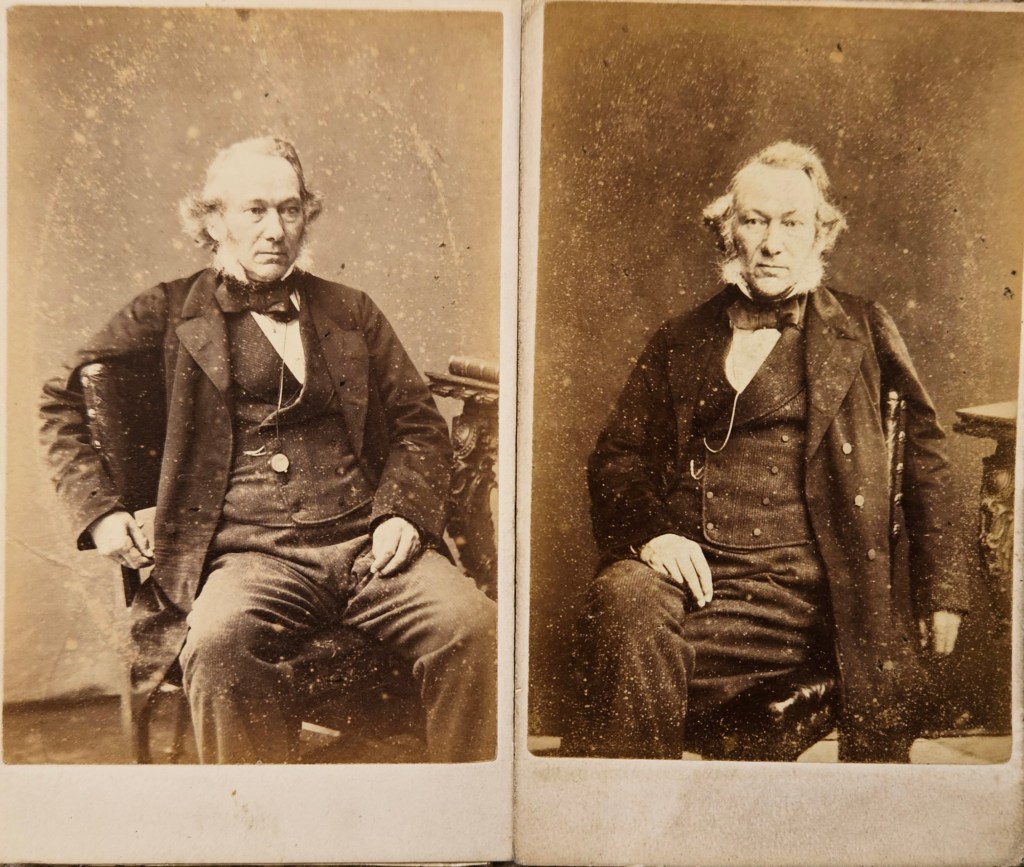

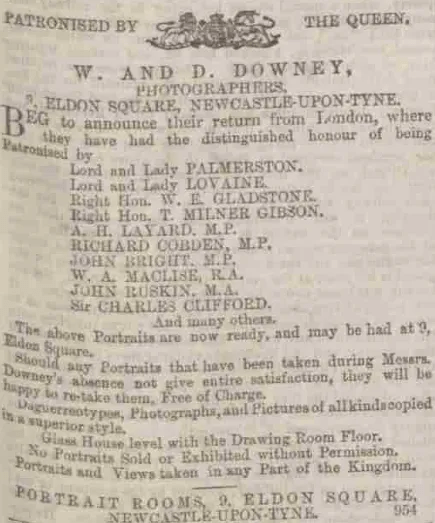

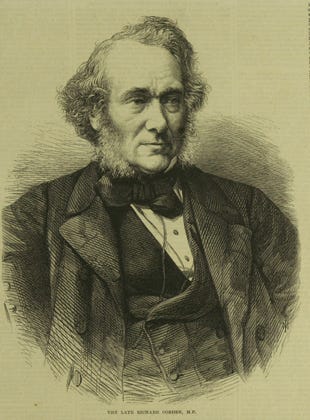

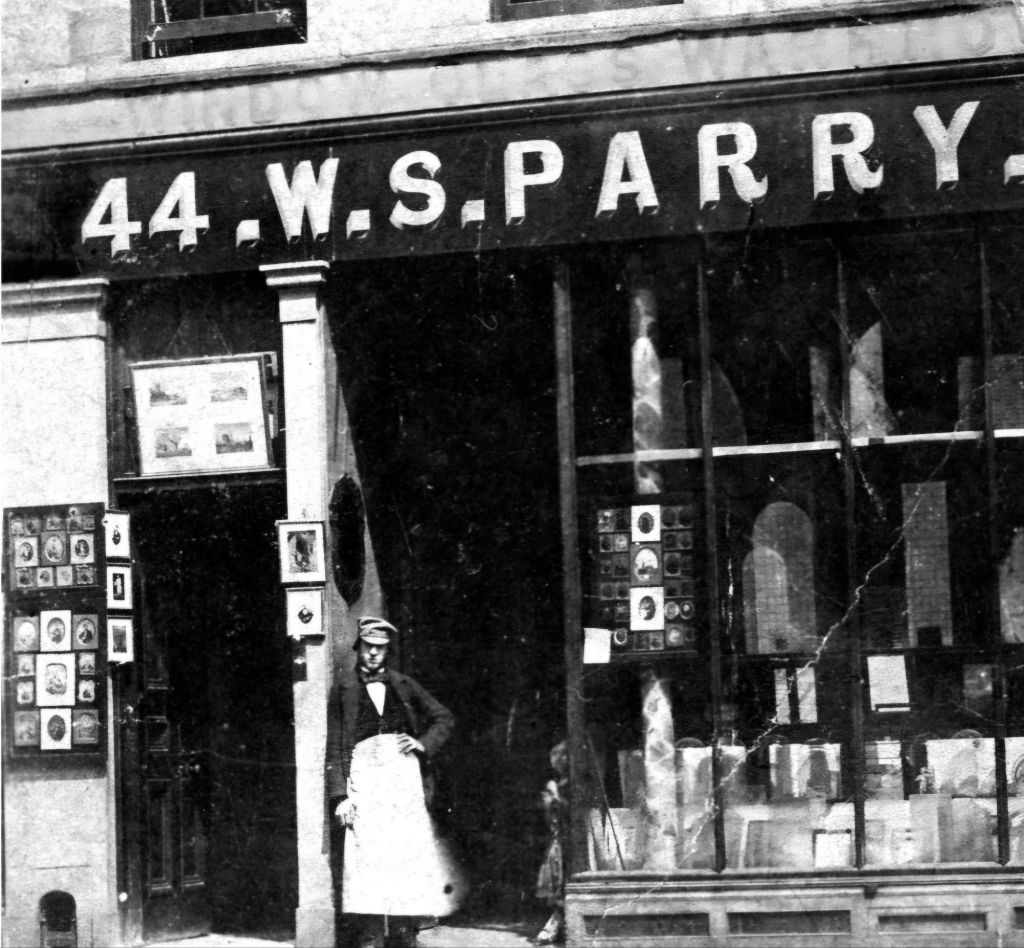

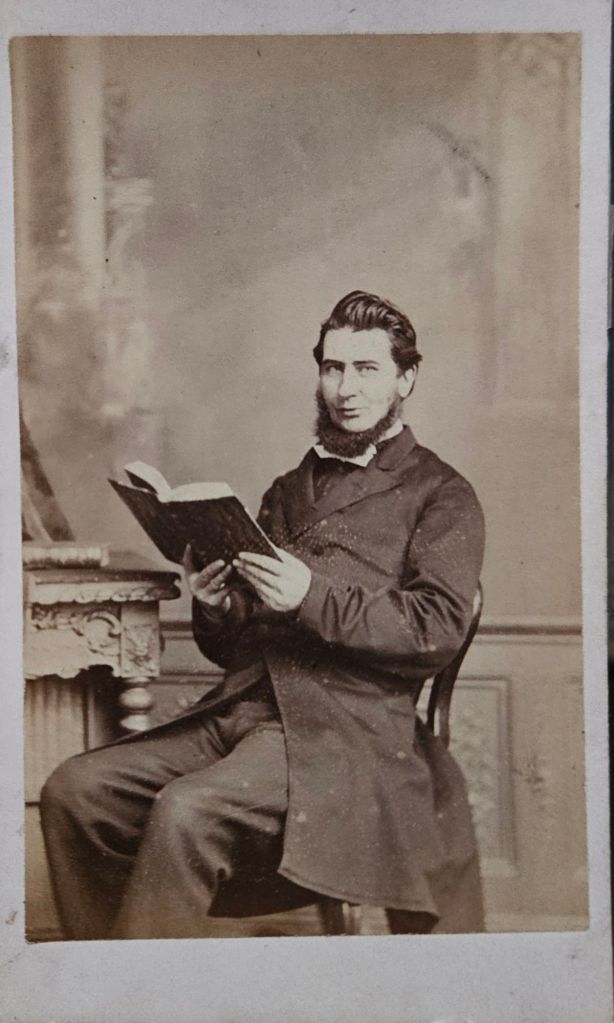

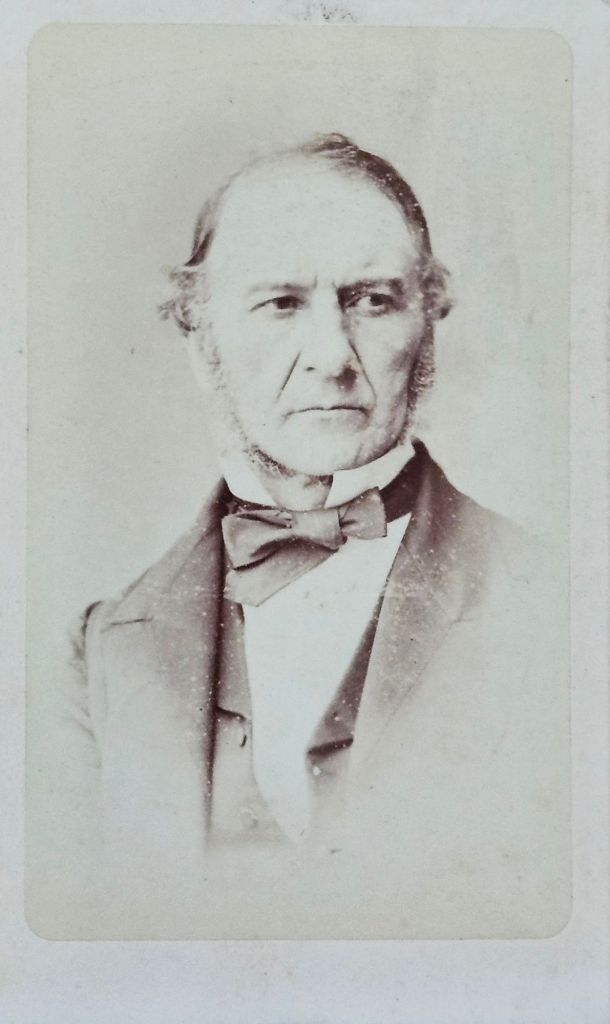

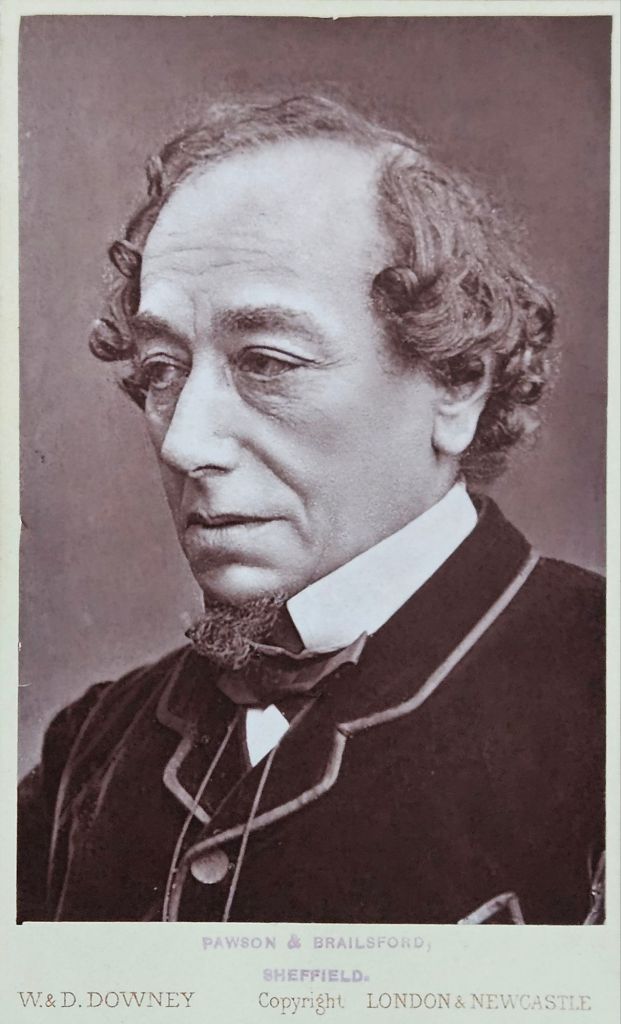

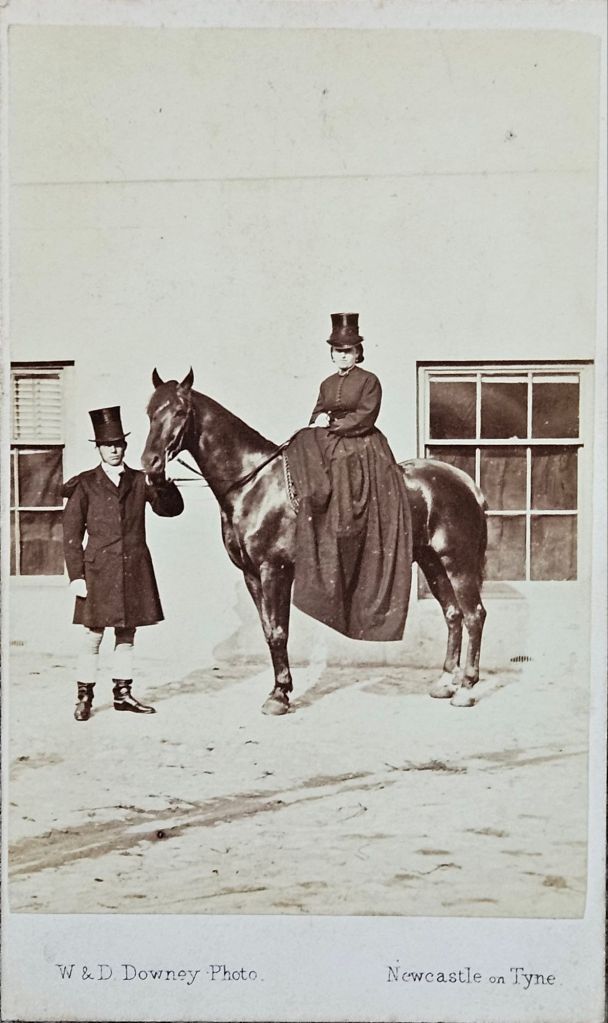

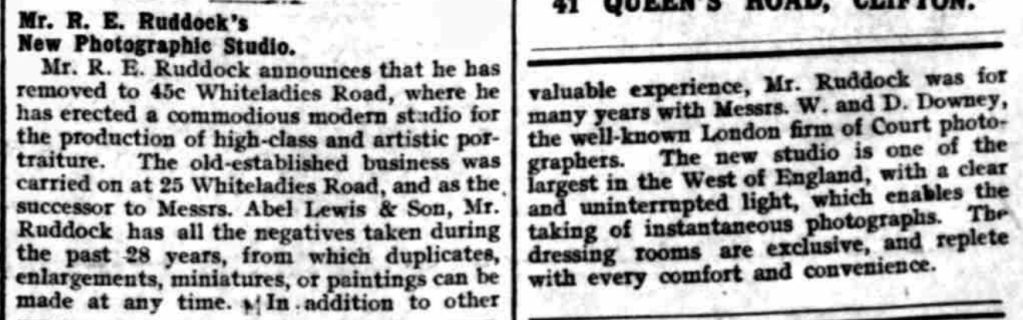

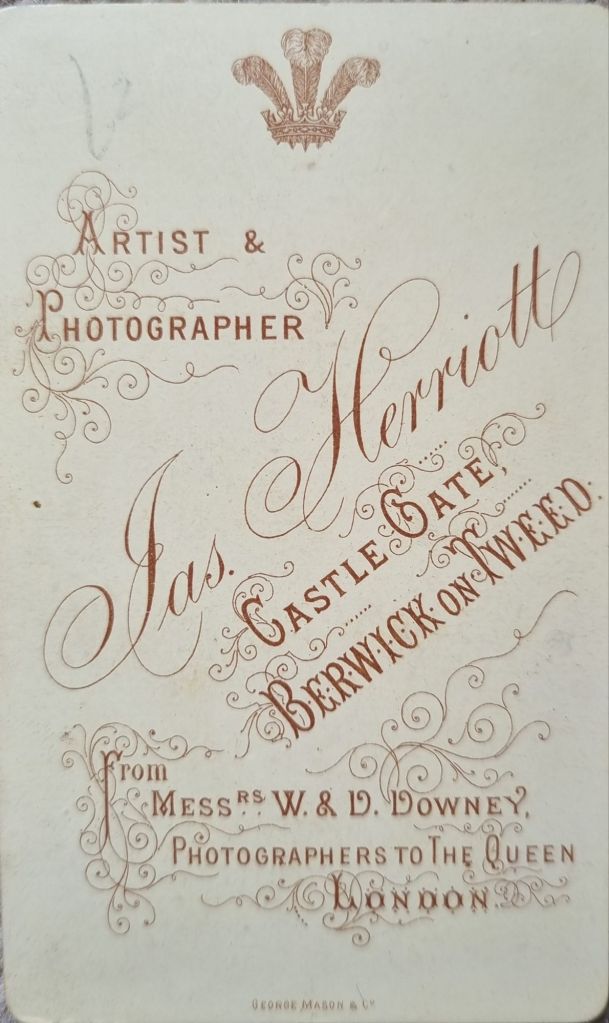

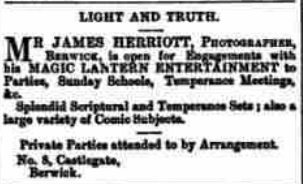

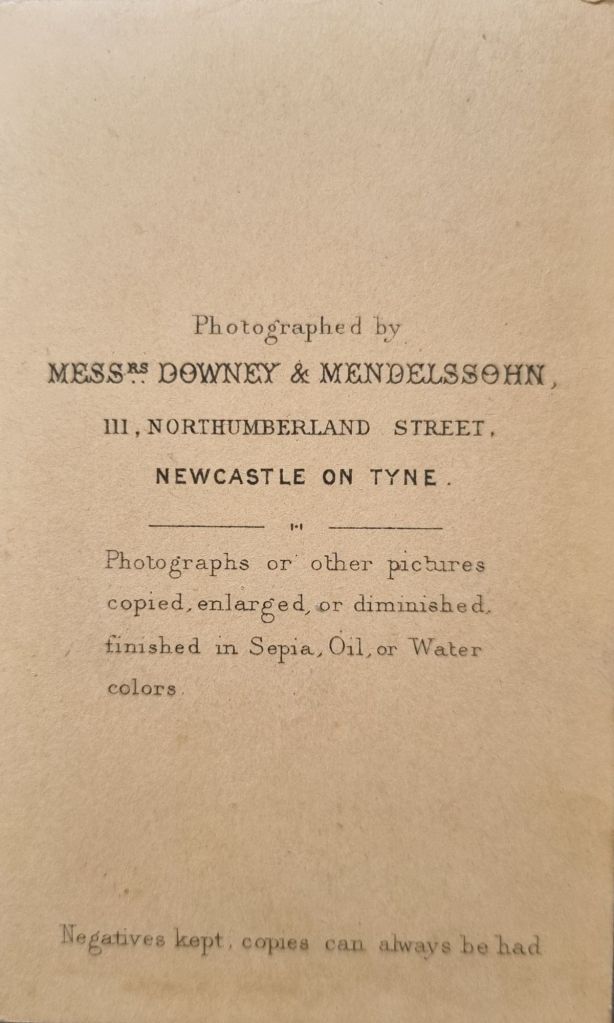

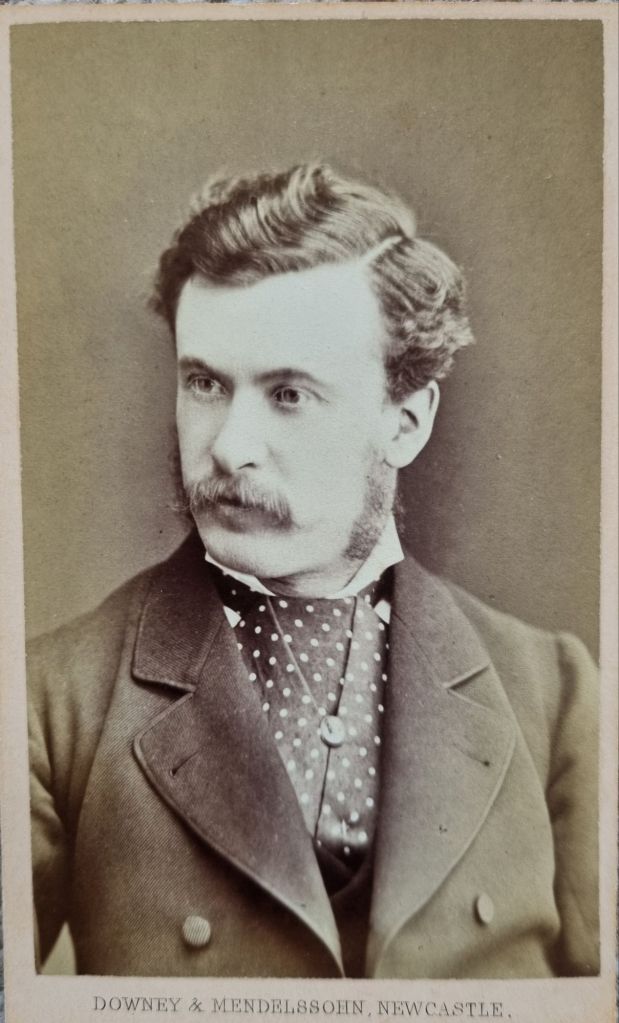

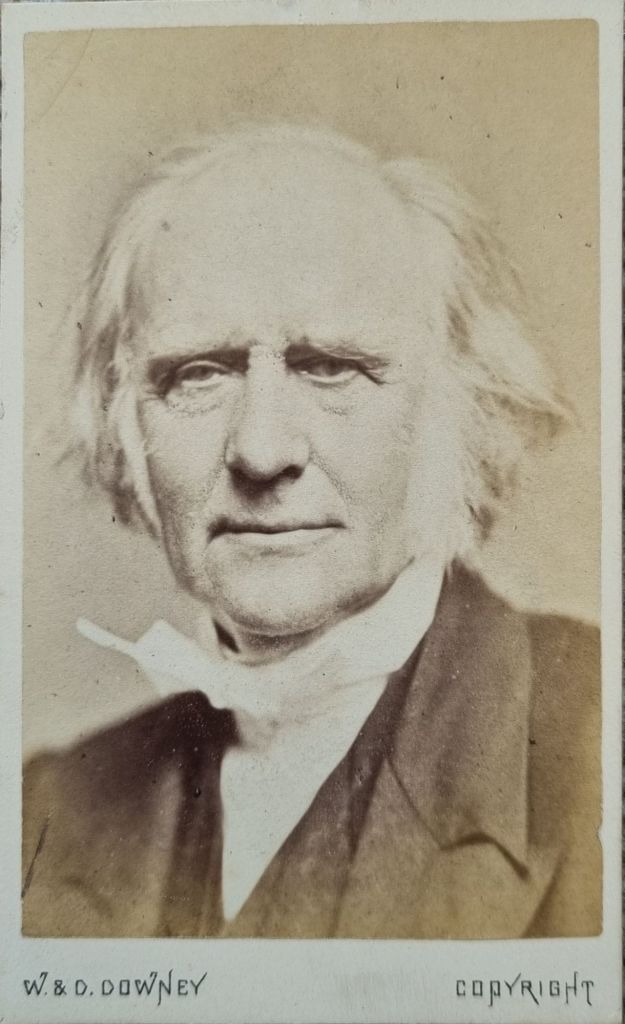

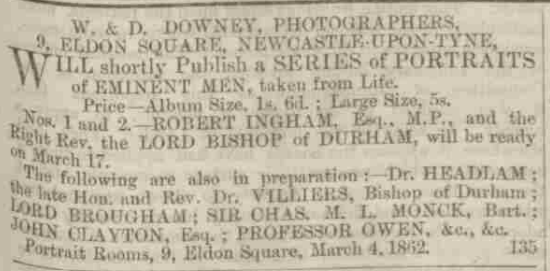

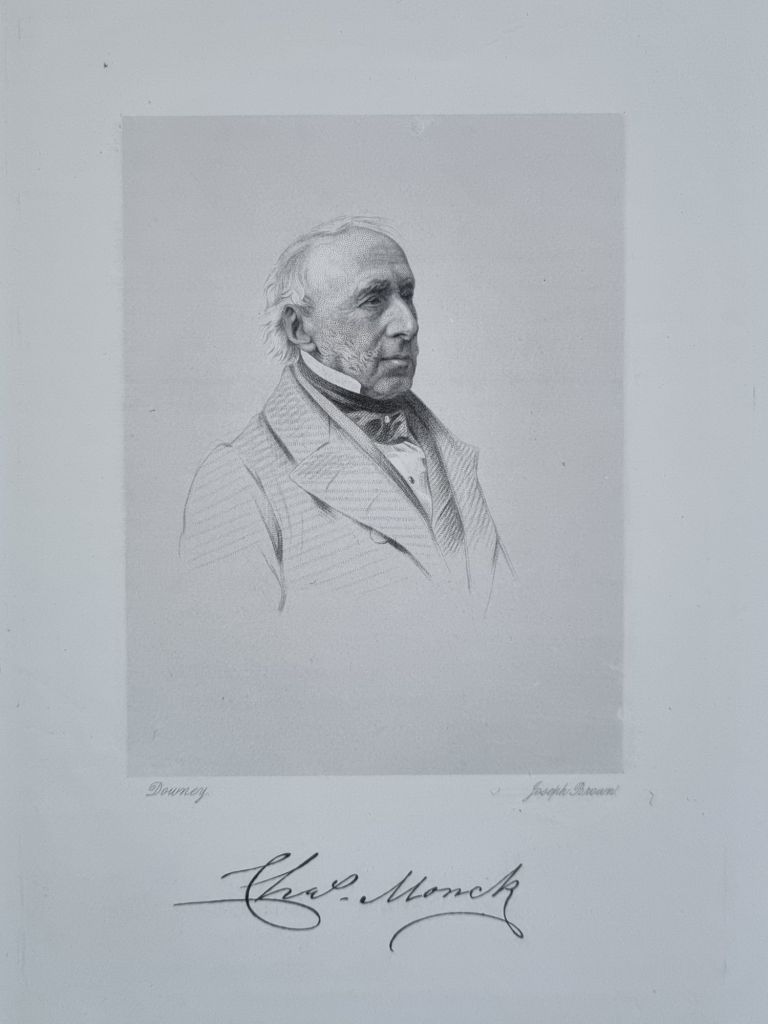

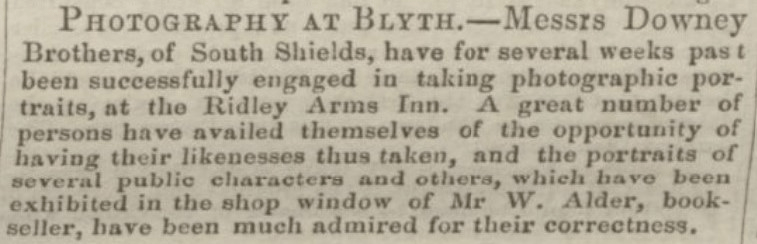

As regular readers will know, it was home to William and Daniel Downey’s first studio that opened in the town’s Market Place in September 1856.

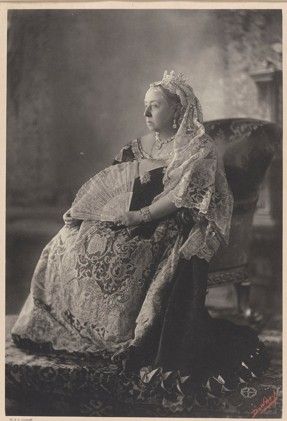

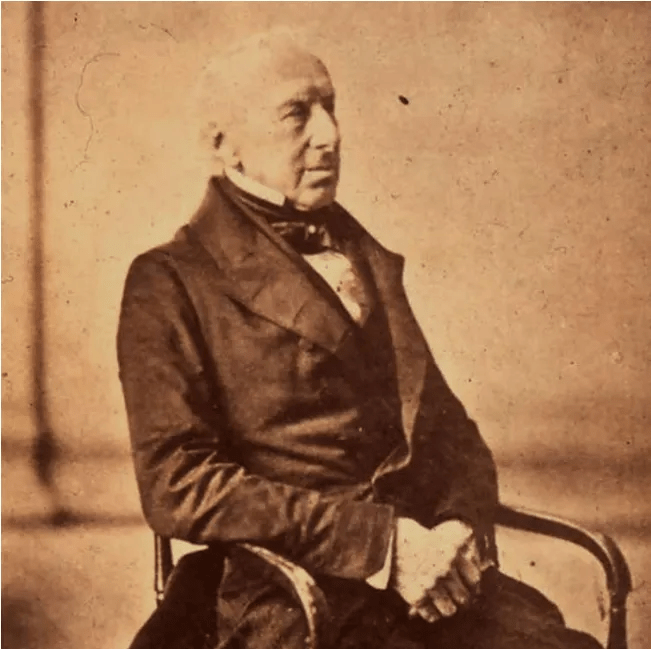

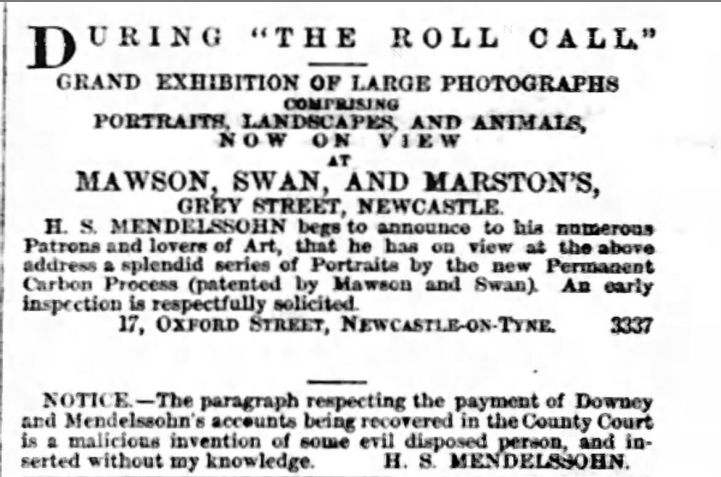

The brothers’ firm, W. & D. Downey, went on to become known worldwide for its portraits of Queen Victoria and the British royal family.

As well as commercial photographers, skilled amateurs were also active in South Shields as revealed in new research by Rebecca Sharpe, co-curator of the Brian May Archive of Stereoscopy (Stereo World, vol. 51, no. 3 / Nov-Dec 2025 and no. 4 / Jan-Feb 2026).

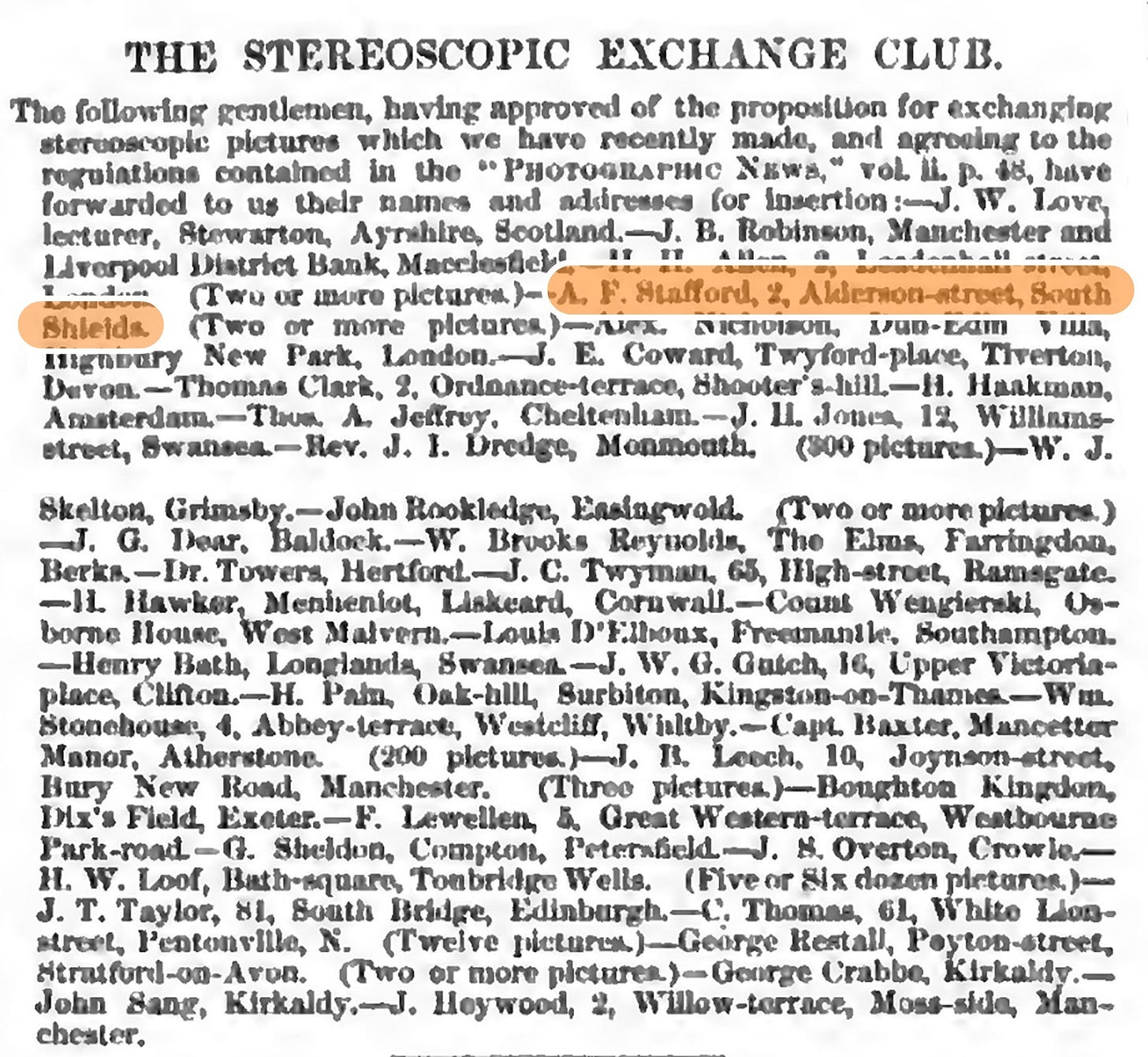

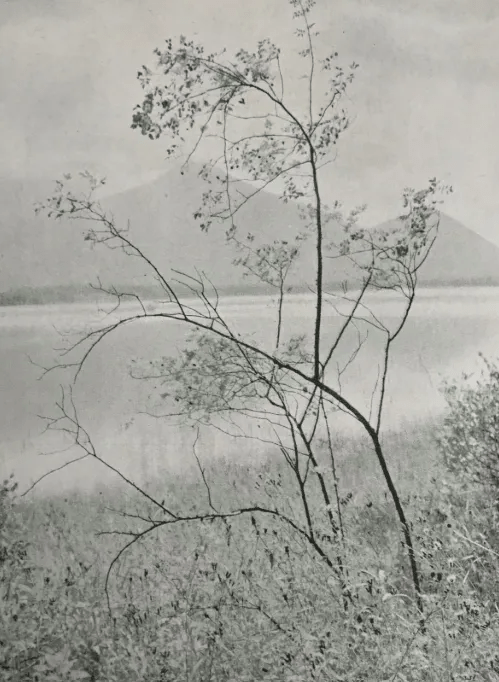

In March 1859, Thomas Crookes, editor of The Photographic News, put forward to readers the idea of exchanging stereoscopic (or 3D) views.

The following month, a list of gentlemen’s names was published as willing participants in what became known as ‘The Stereoscopic Exchange Club.’

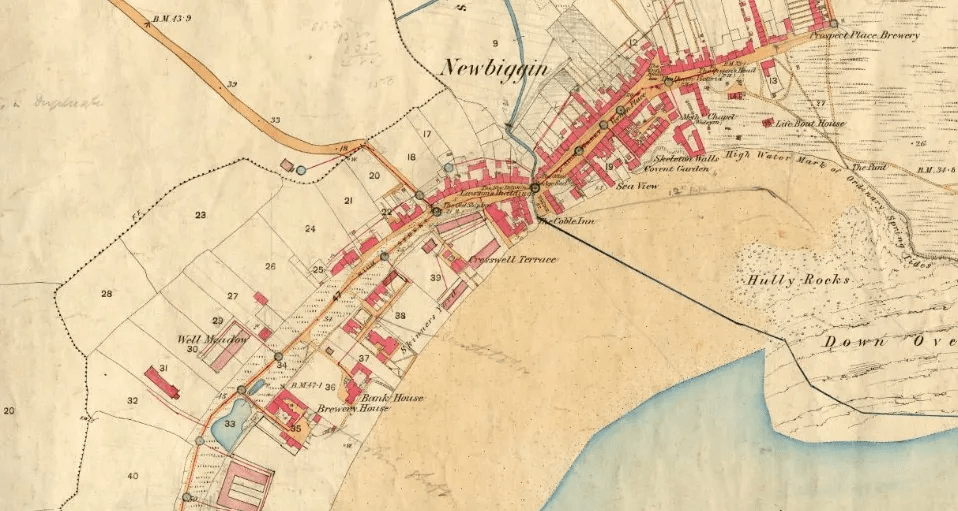

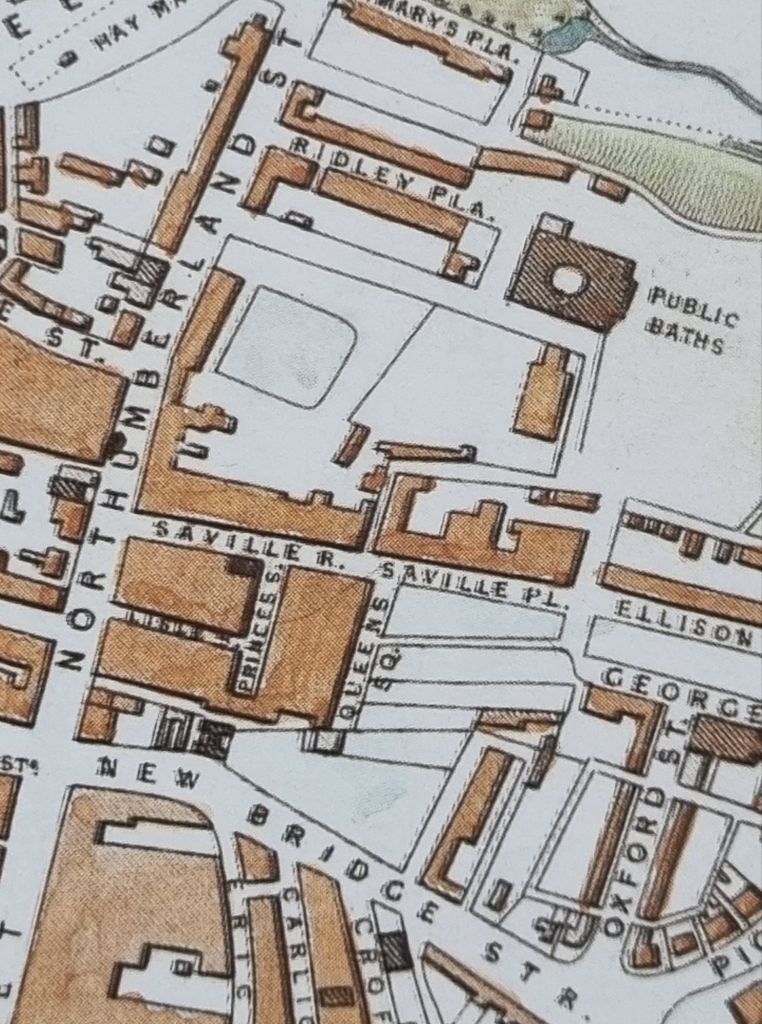

Among its founding members was ‘A.F. Stafford of 2 Alderson Street, South Shields.’

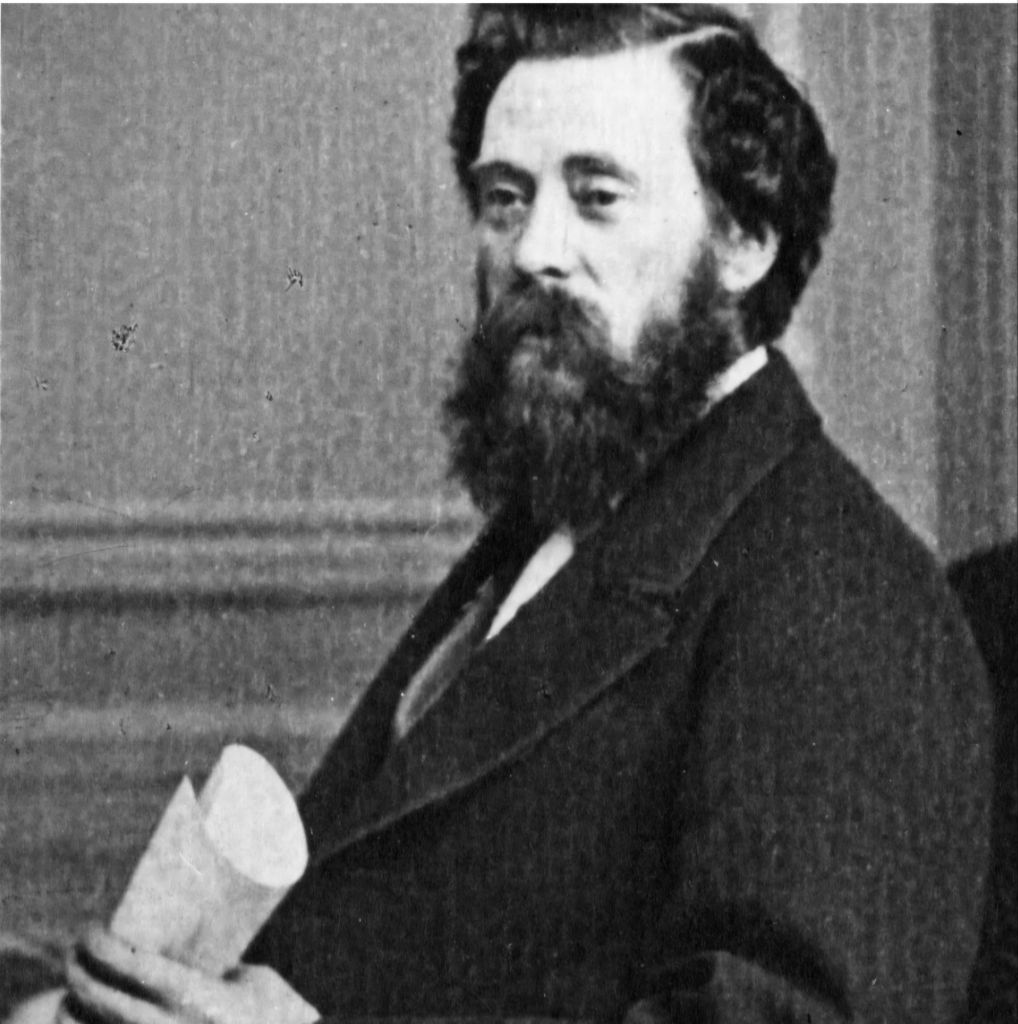

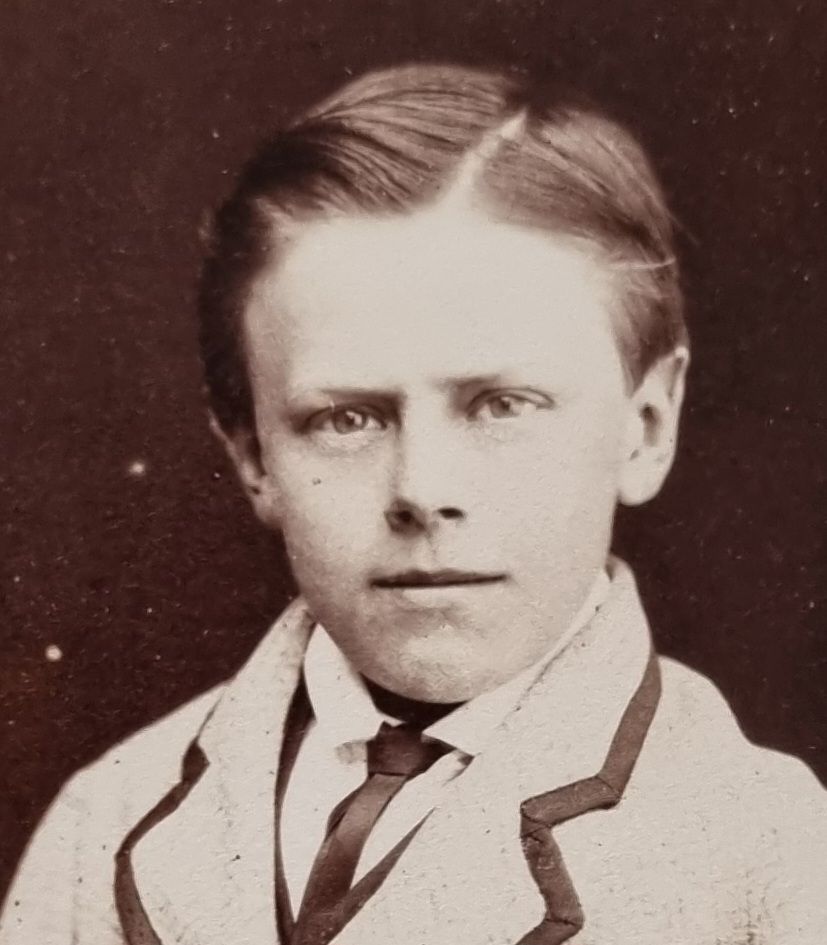

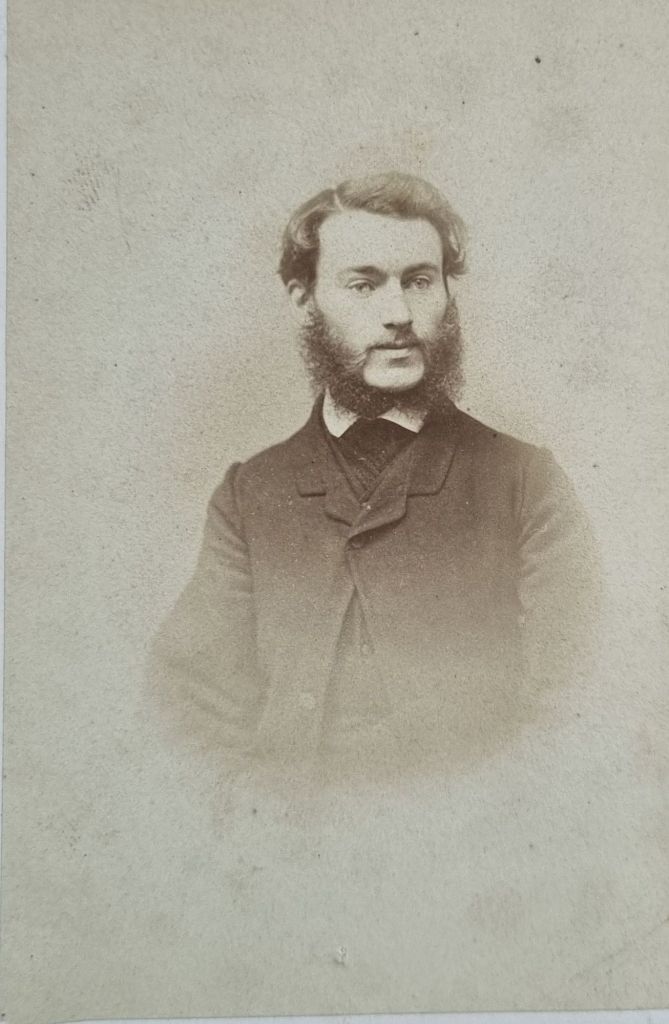

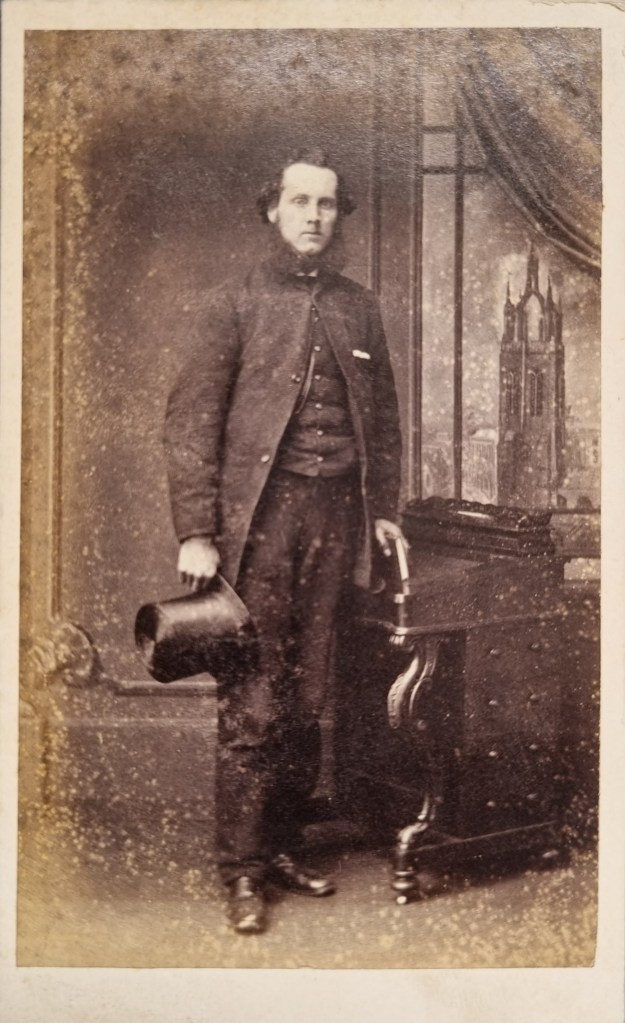

According to the 1861 Census, Anthony Ford Stafford (1822-1910) was a ‘ship builder’s agent’ living with his wife Maria in the Westoe district of the town.

As to his photography, the columns of The Photographic News reveal that he was both knowledgeable and accomplished.

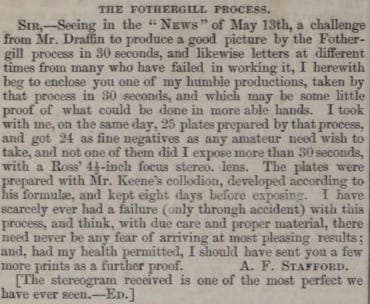

In a contribution to the paper’s ‘Photographic Notes and Queries’ column (5th August 1859), Stafford described his experience of using the newly-announced dry plate Fothergill Process.

This account also reveals important details about his photographic practice including his use of a “Ross 4 1/2 inch focus stereo lens.”

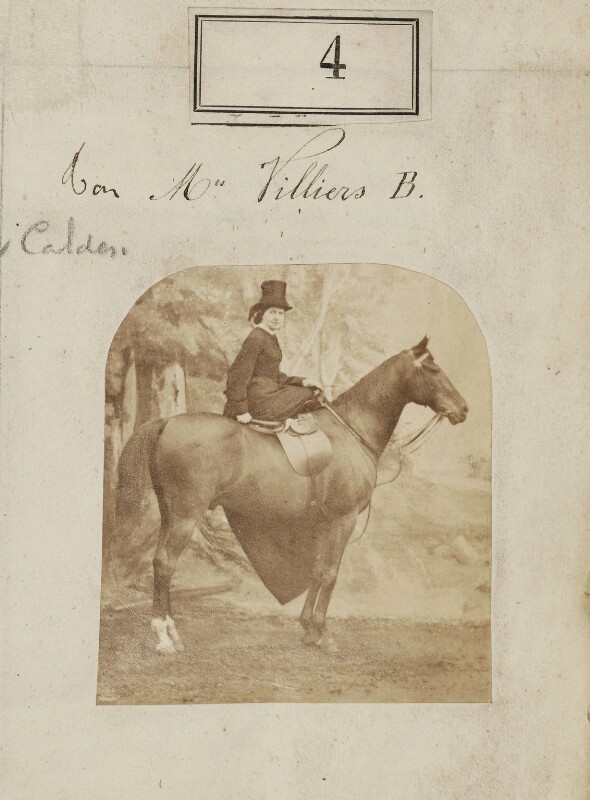

In a note at its conclusion, editor Thomas Crookes added: “The stereogram received is one of the most perfect we have ever seen” though no mention of the subject was given.

In what might be a complete coincidence, a W. & D. Downey newspaper advert appeared the very next day offering for sale “stereoscopic views of the village of Westoe.”.

Taken together though, these two pieces of evidence at least raise the possibility that A.F. Stafford was supplying Downey’s with high-quality stereoscopic views.

As to whether they knew each other, their paths may well have crossed in other roles they undertook in the South Shields community

For example, Stafford was secretary of the Mechanics Institute whilst both Downey brothers were committee members of the Working Men’s Institute.

Within a few years though, their lives had moved in different directions.

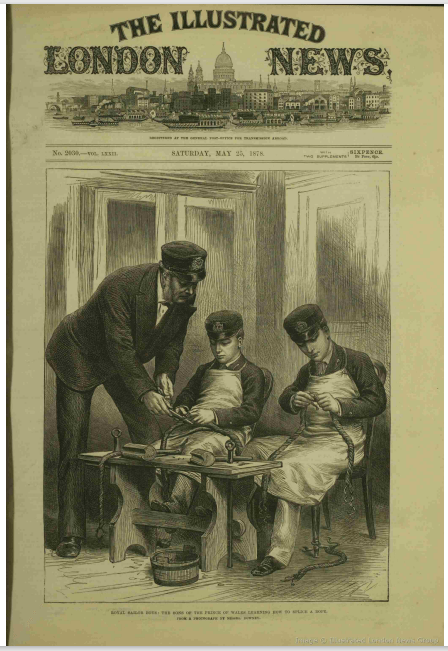

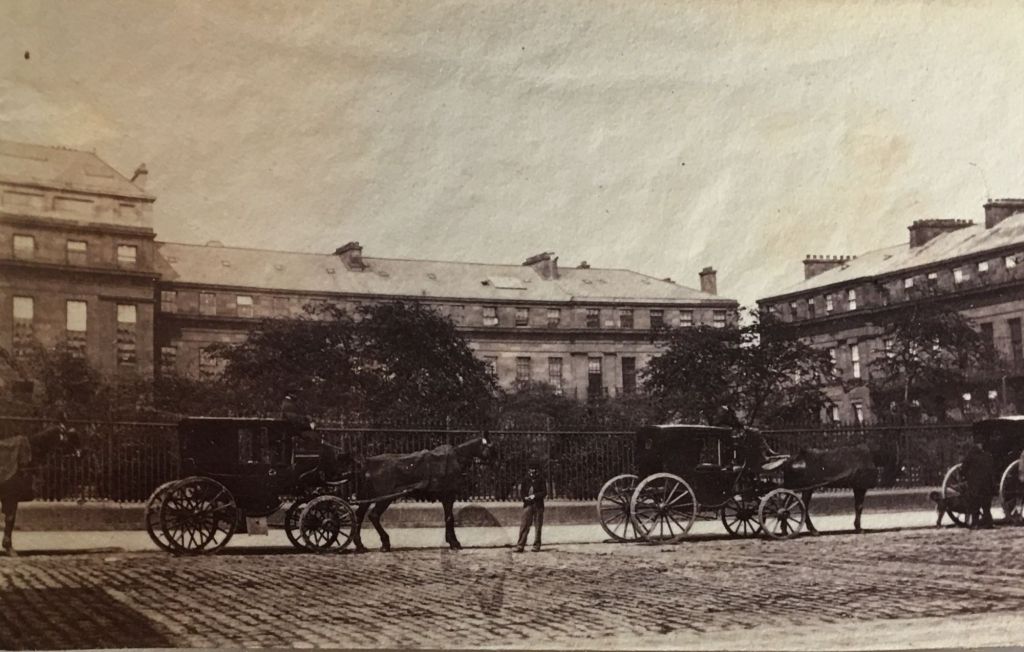

In March 1863, South Shields celebrated the royal wedding of the Prince and Princess of Wales with a public ball in the hall of the Mechanics Institute that A.F. Stafford helped organise.

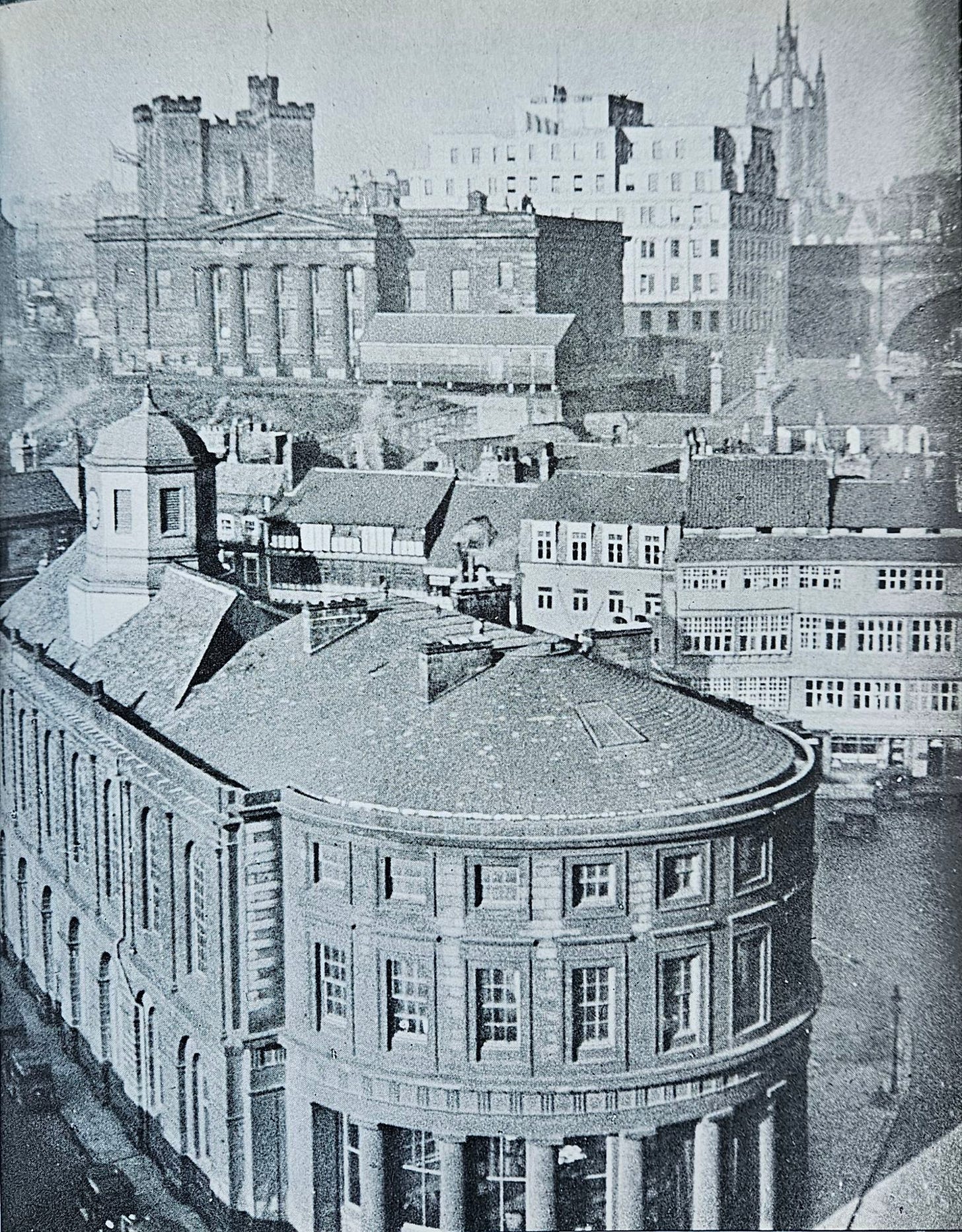

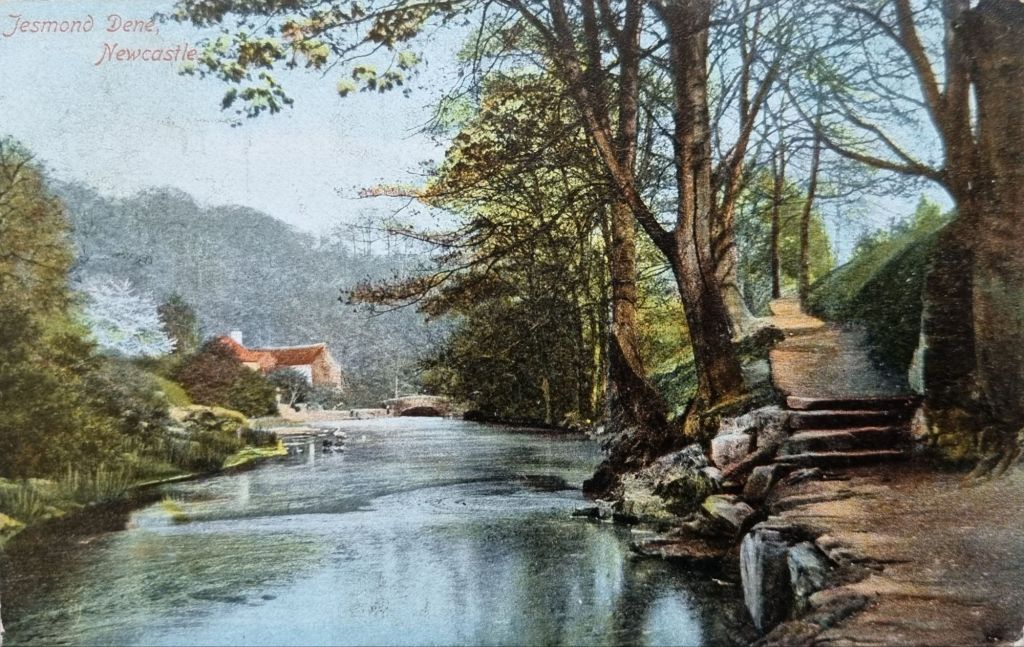

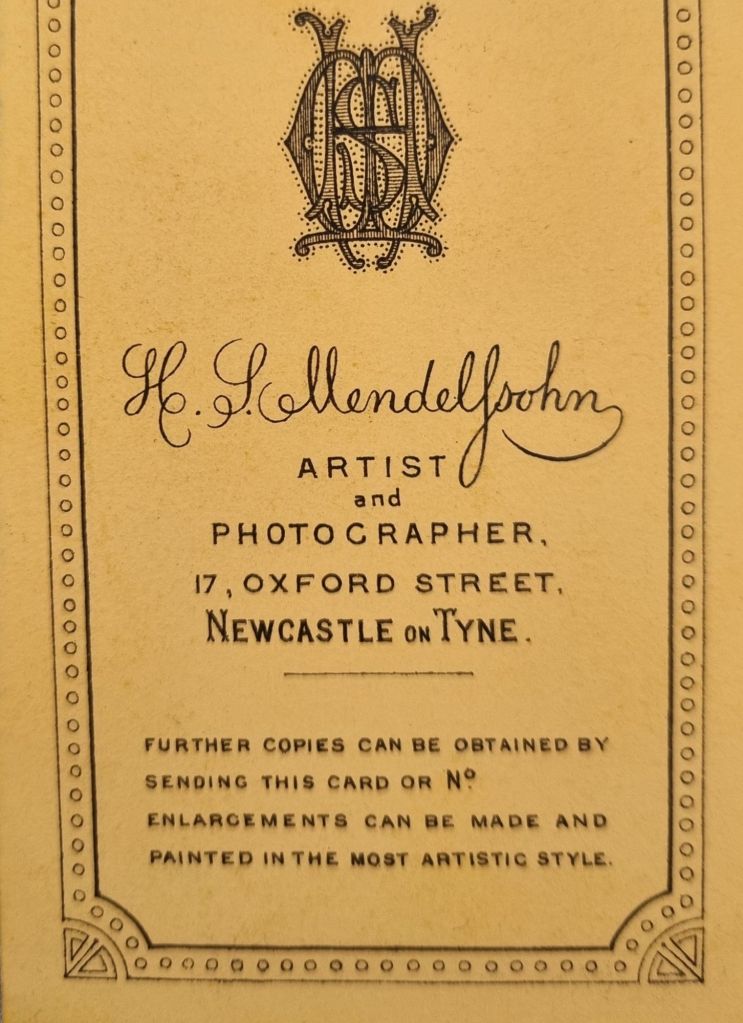

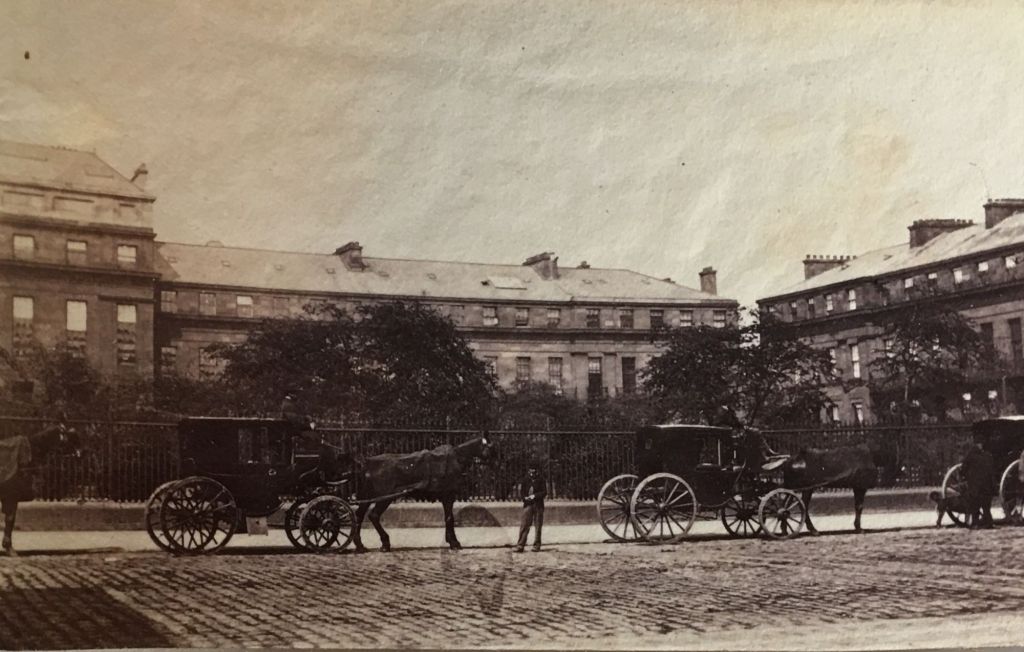

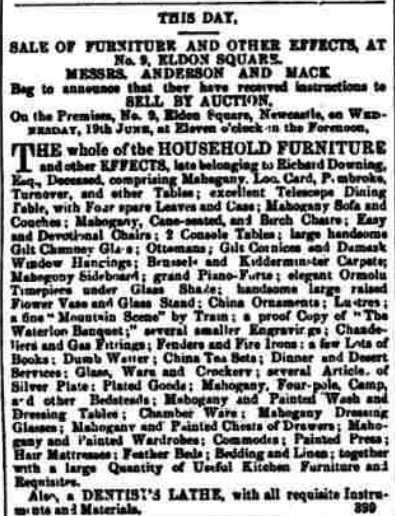

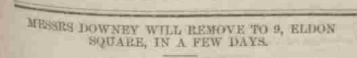

By contrast, the Downey brothers had opened a studio in Newcastle upon Tyne and were soon photographing members of the royal family such as Alexandra, Princess of Wales with her daughter Louise.

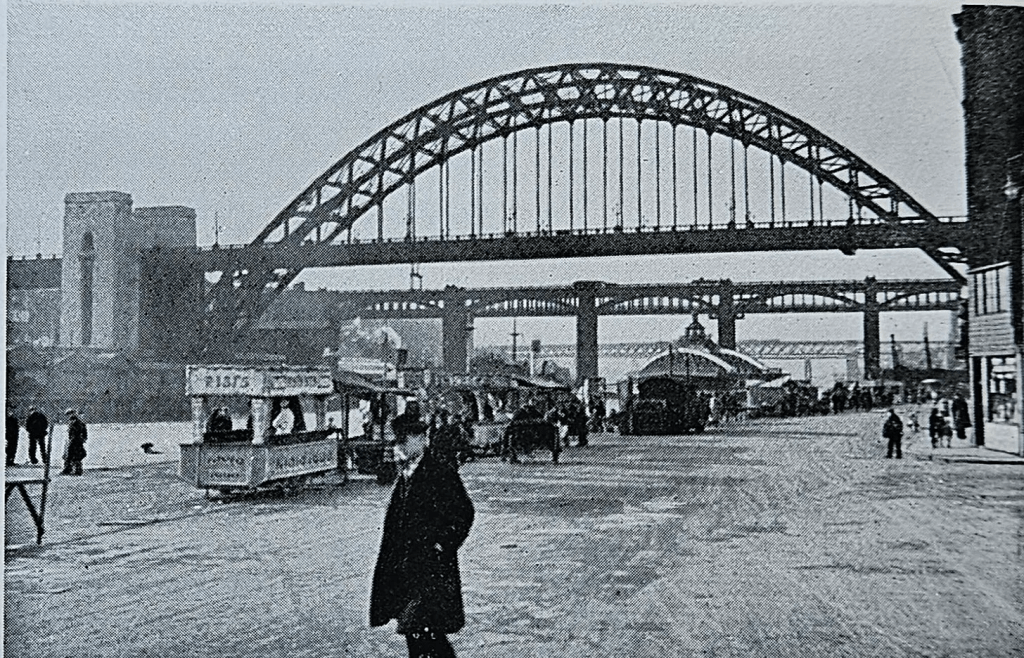

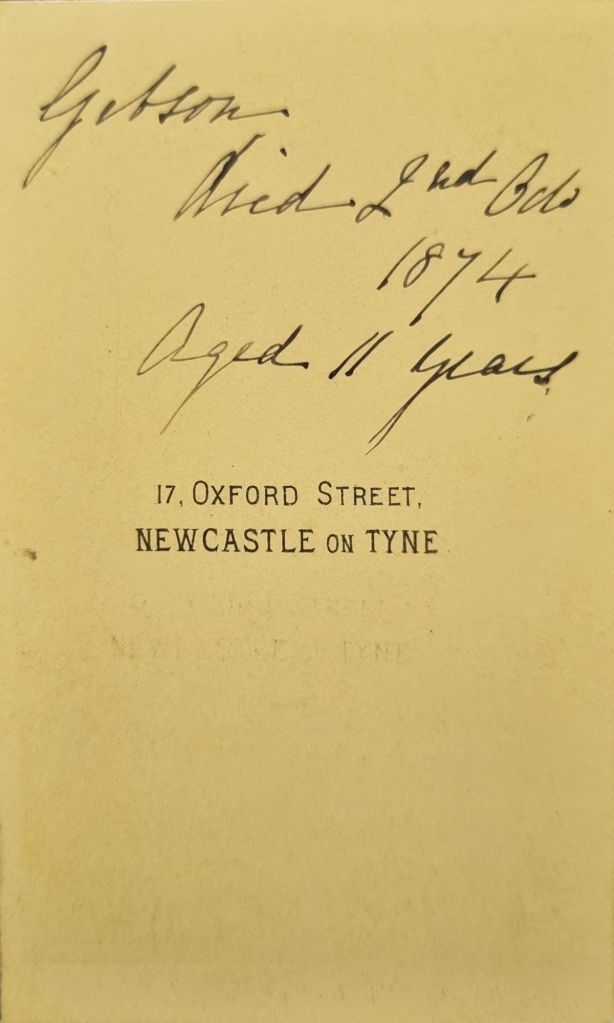

In the search for more clues about A.F. Stafford’s photography, I was delighted to locate a cache of his personal papers in the collection of the Tyne & Wear Archives (DX1016).

This reveals more about his business dealings centred around shipping on the River Tyne, but sadly there was no further evidence or any examples of his photography.

As for the Stereoscopic Exchange Club of which Stafford had been a founding member, it continued for a few years until running out of steam.

If this post has whetted your appetite, Rebecca Sharpe’s research about the Stereoscopic Exchange Club with examples of its members’ stereos features in a talk she gave last week for the Royal Photographic Society Historical Group.

She shared the event with Julie Gibb of National Museums Scotland whose research into the United Stereoscopic Society featured in an earlier Pressphotoman post (Jigsaw Pieces – 8th December 2025).

‘Exchanging Stereoscopic Views’ – RPS Historical Group – 10th February 2026

Leave a comment