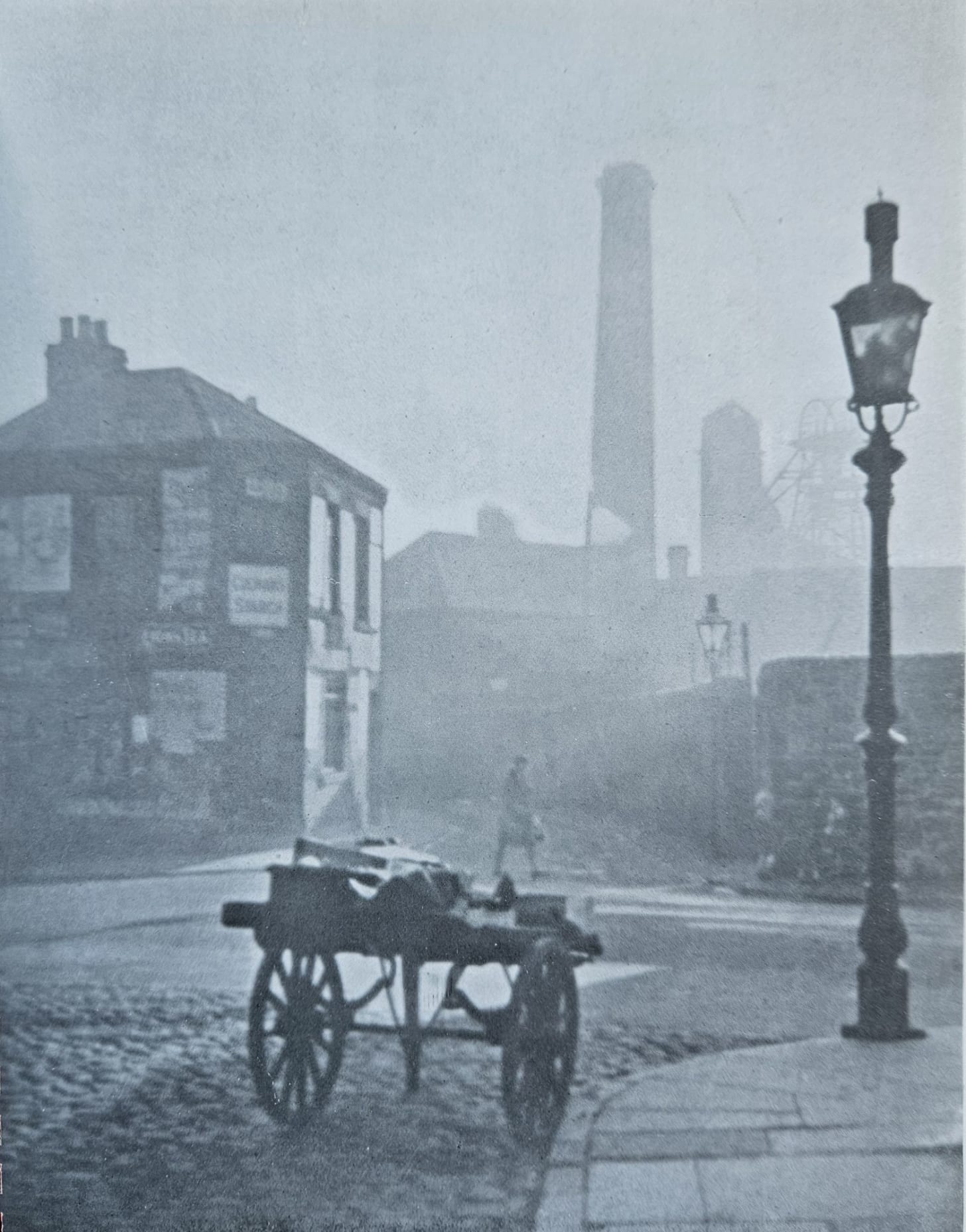

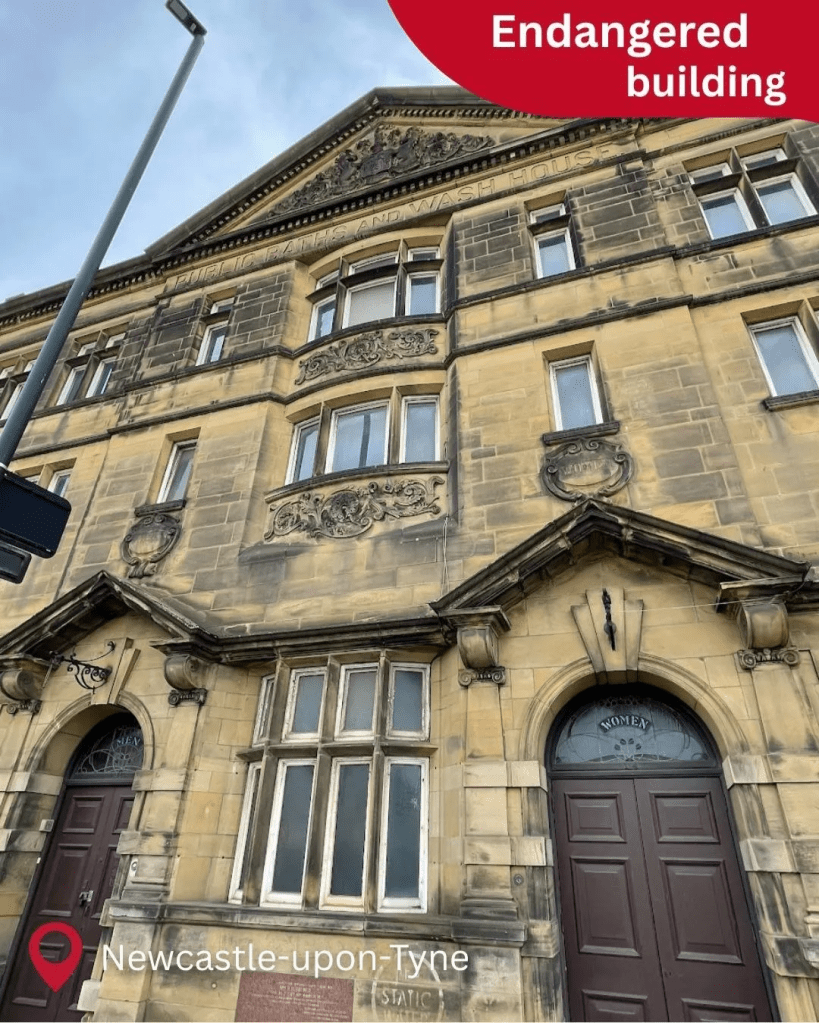

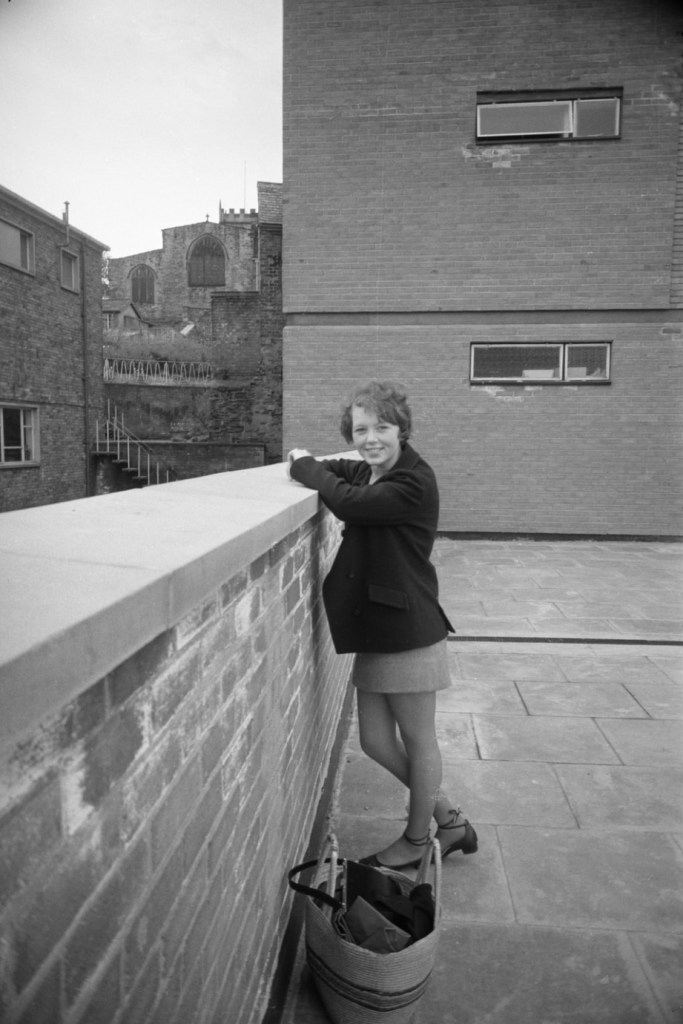

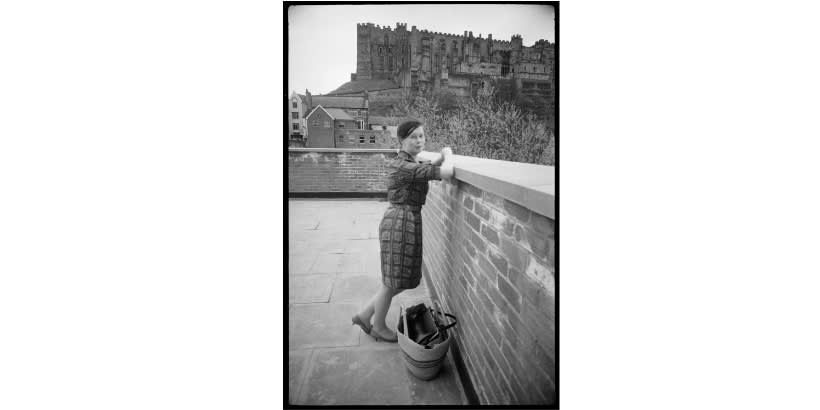

The work of architectural photographer Ursula Clark (1940-2000) is primarily captured in publications produced by Oriel Press of Newcastle upon Tyne.

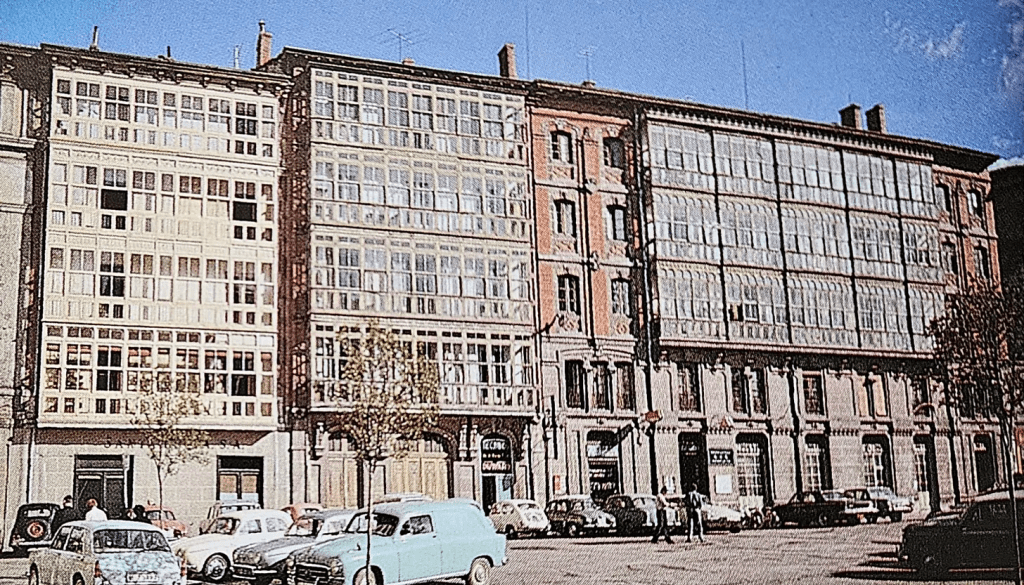

These include the series of Oriel Guides to England, Scotland, France, Italy and Spain (1963-1969) as well as its Historic Architecture of … series featuring Newcastle upon Tyne (1967), Northumberland (1969), Leeds (1969) and County Durham (1971).

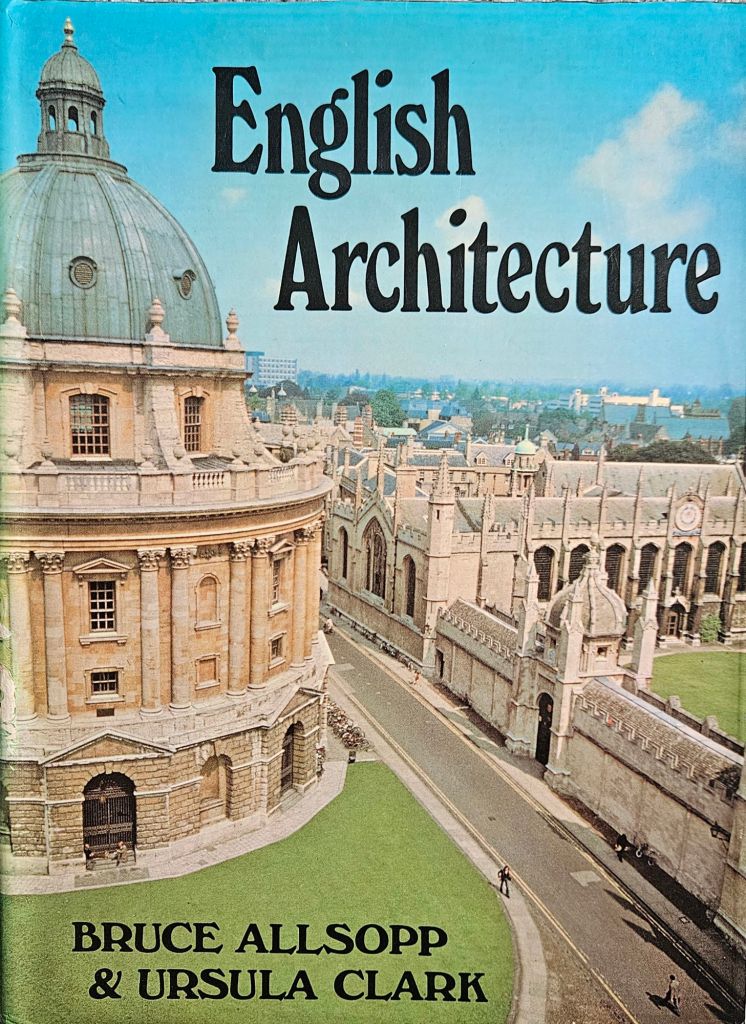

However, these books, many co-authored with Oriel’s Bruce Allsopp, and the quality of Ursula Clark’s images attracted wider attention.

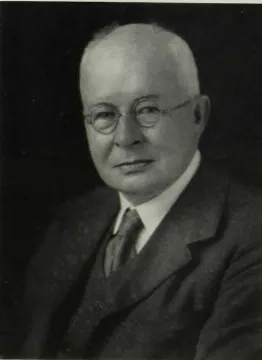

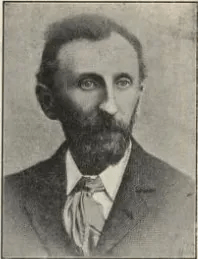

One of their admirers was the celebrated town planner Thomas Sharp (1901-1978) whose many books celebrated the heritage of British architecture.

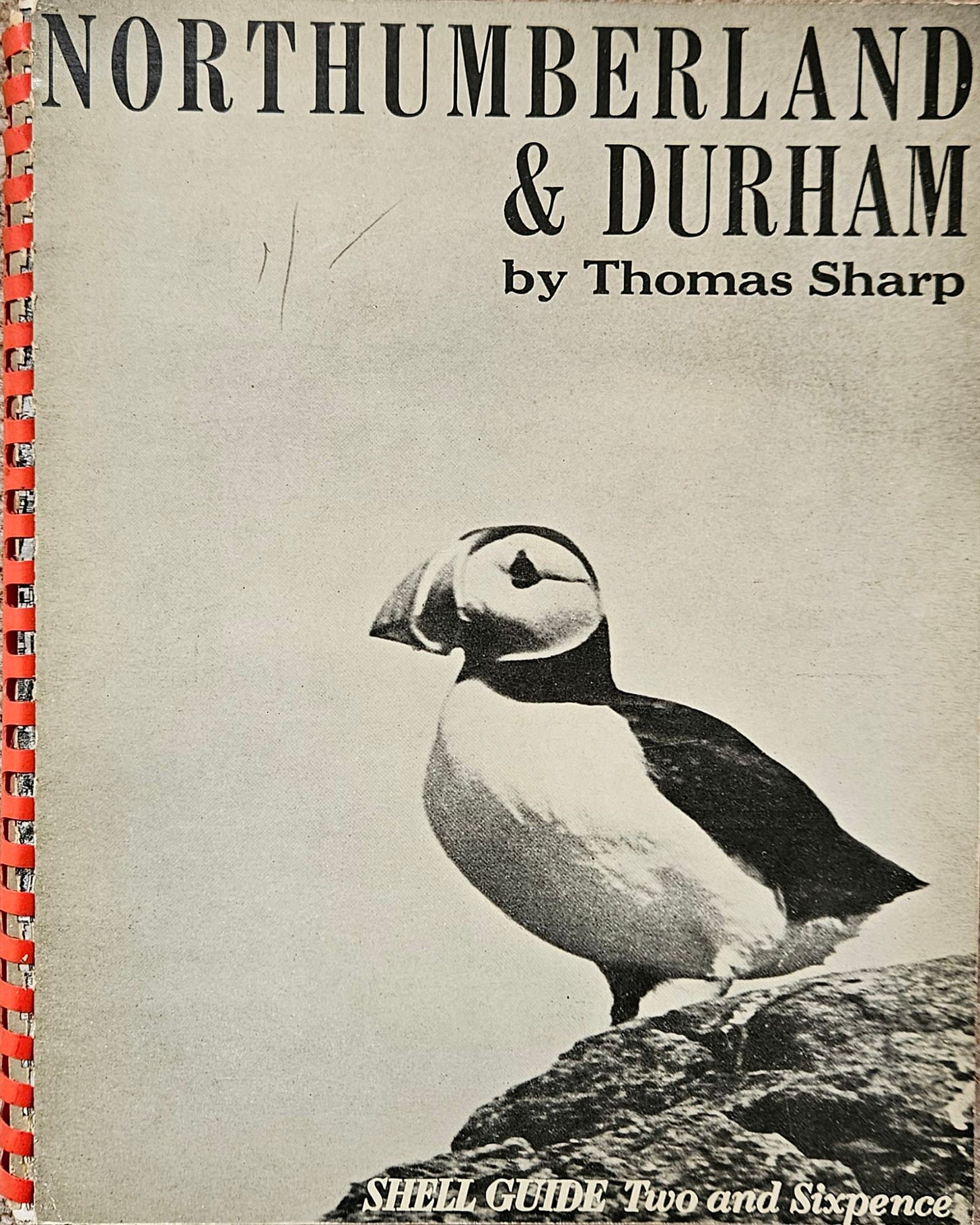

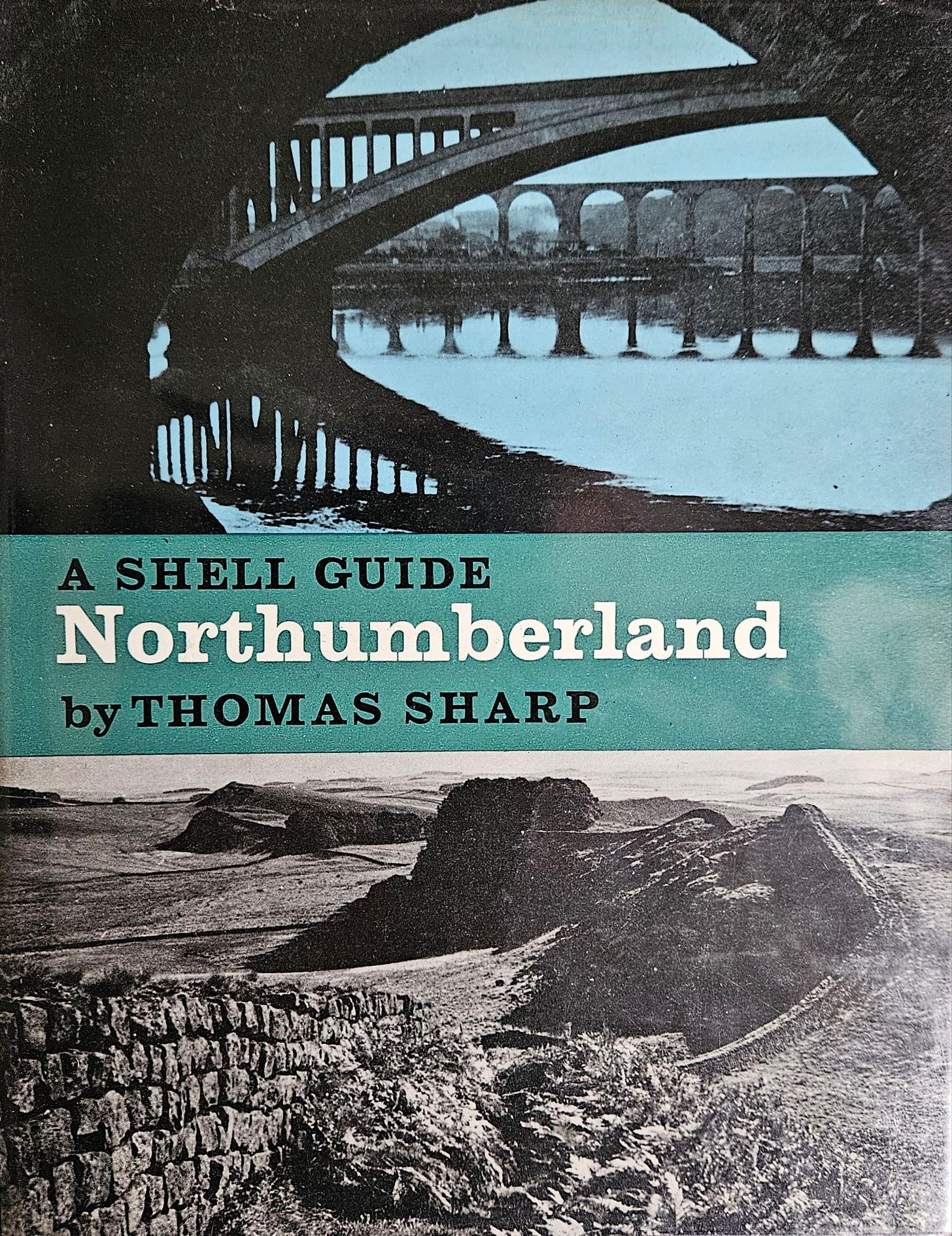

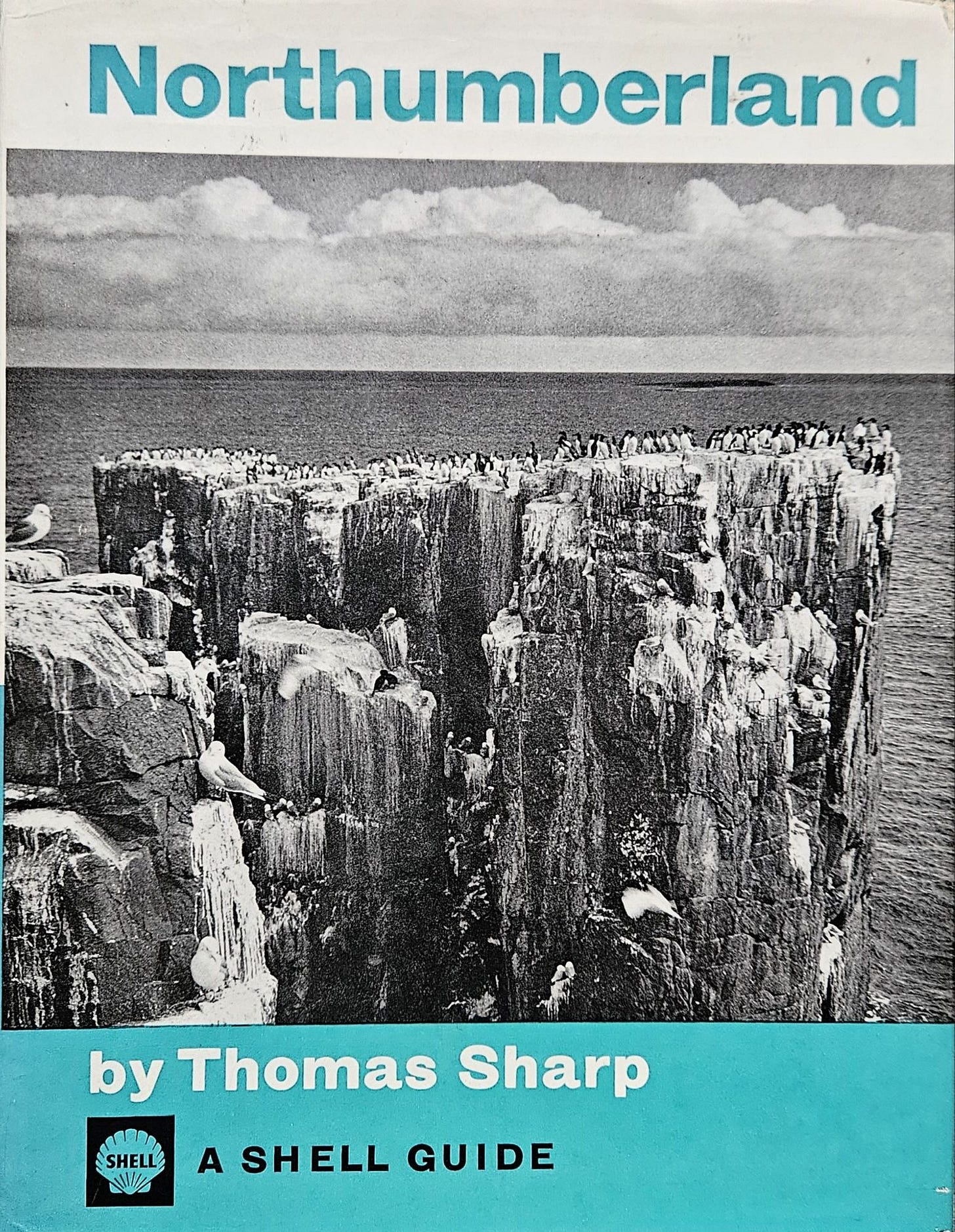

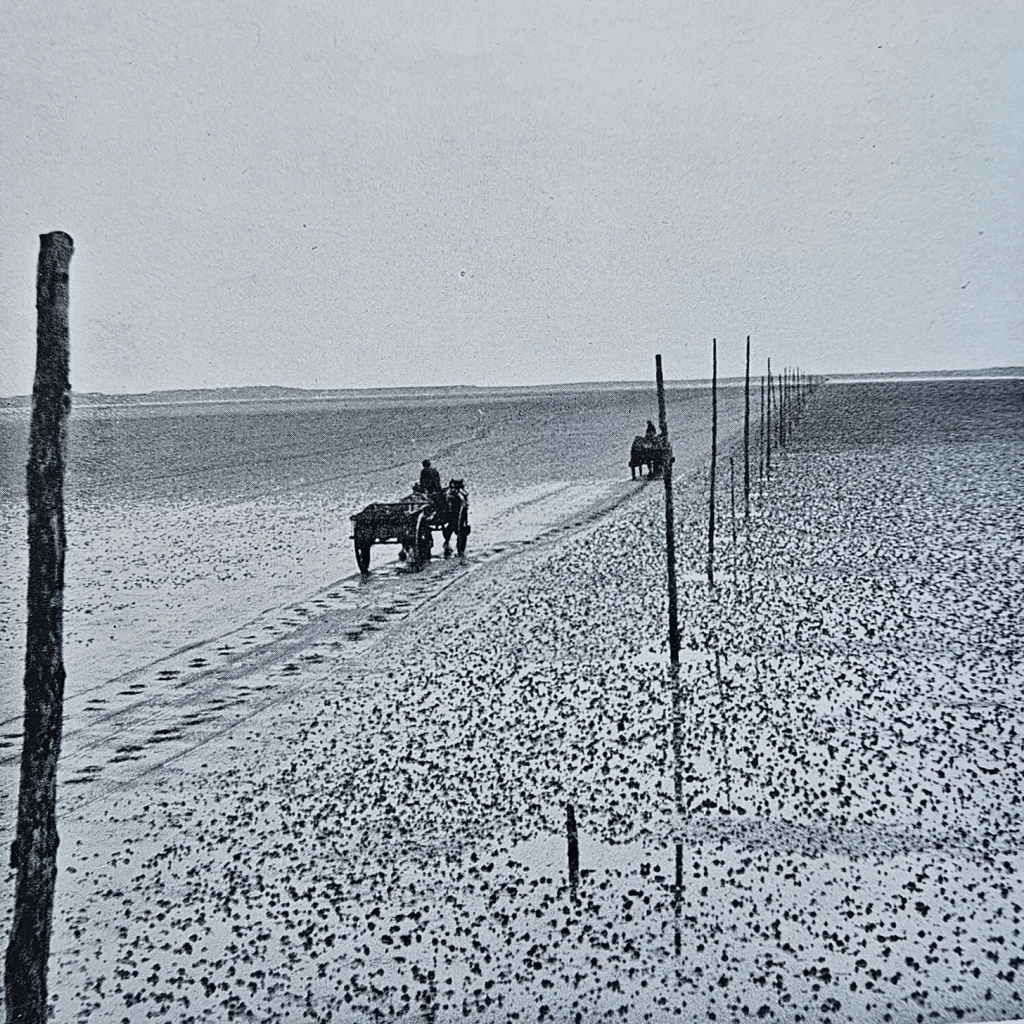

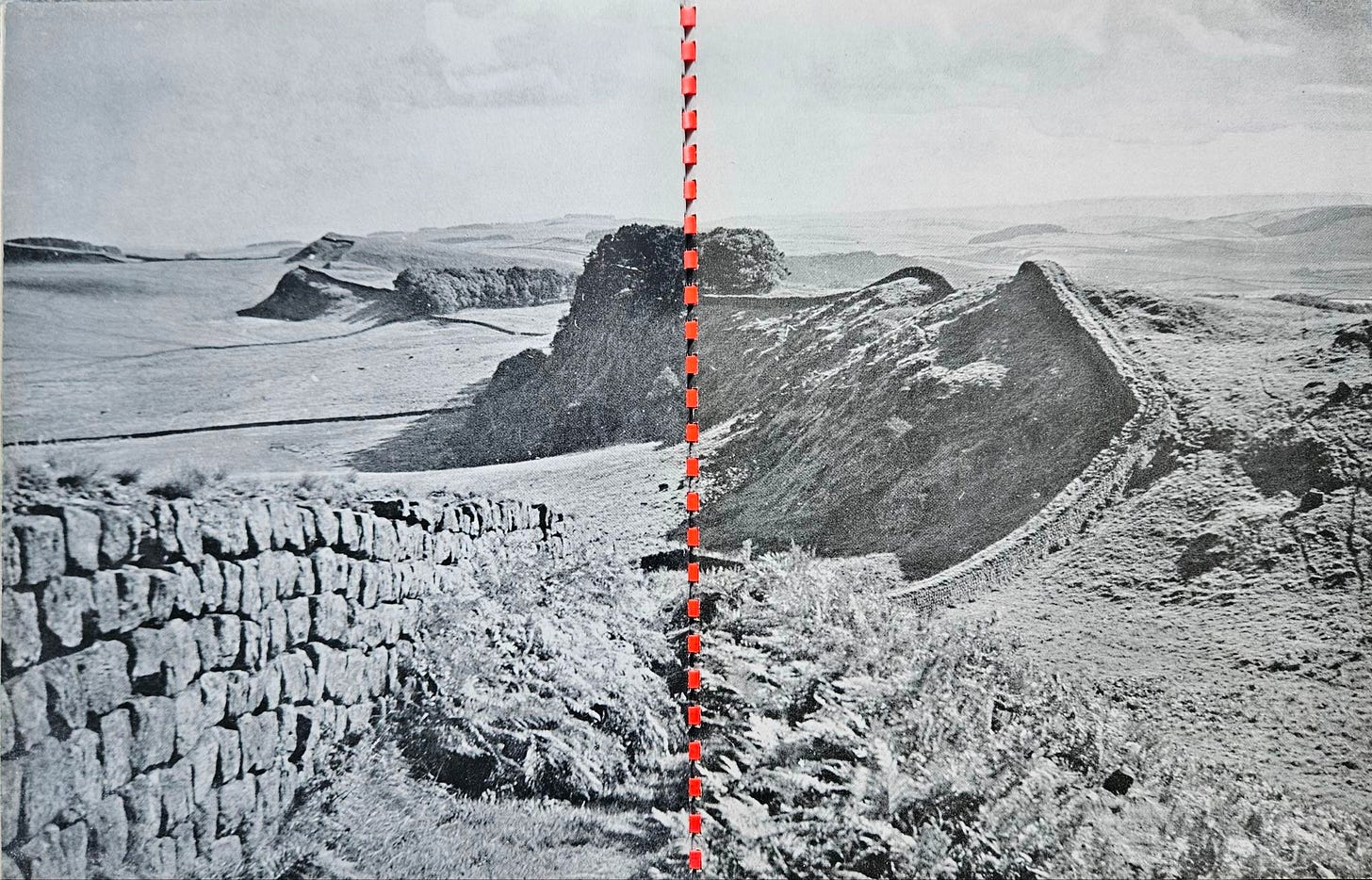

Aimed at motorists and tourists, Sharp had contributed Northumberland & Durham (1937) and Northumberland (1954) to the Shell Guides series masterminded by joint editors John Betjeman and John Piper.

Piper became the series’ sole editor in 1967 and following a request from Faber & Faber, publisher of the Shell Guides, Sharp agreed to revise and update his Northumberland volume for a third edition.

However, correspondence in the Thomas Sharp Archive held by Newcastle University reveals that its production was hindered by a fundamental disagreement about the choice of photographs to be included.

Piper’s biographer Frances Spalding describes Sharp as being “greatly angered” by the issue (Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2009).

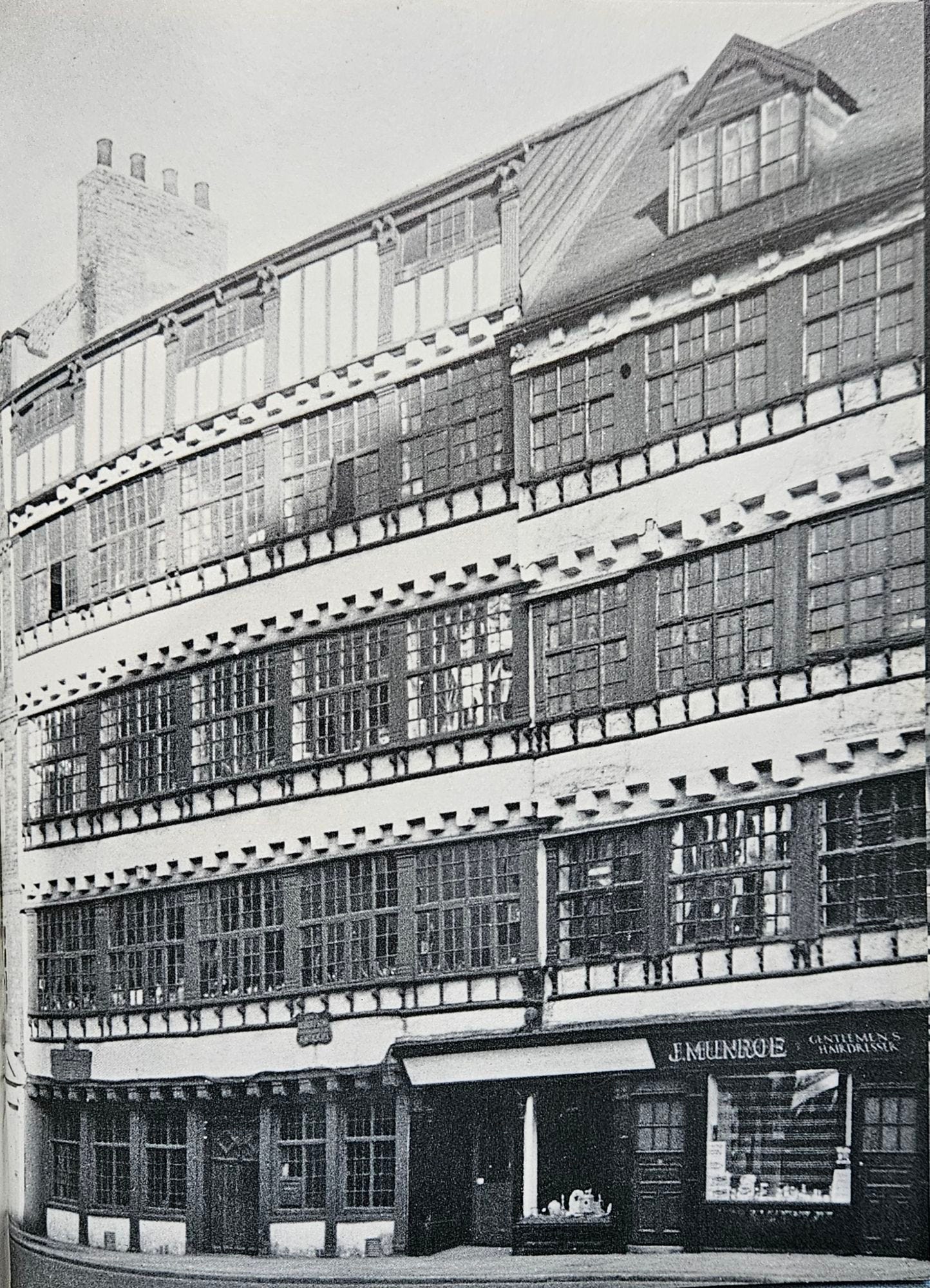

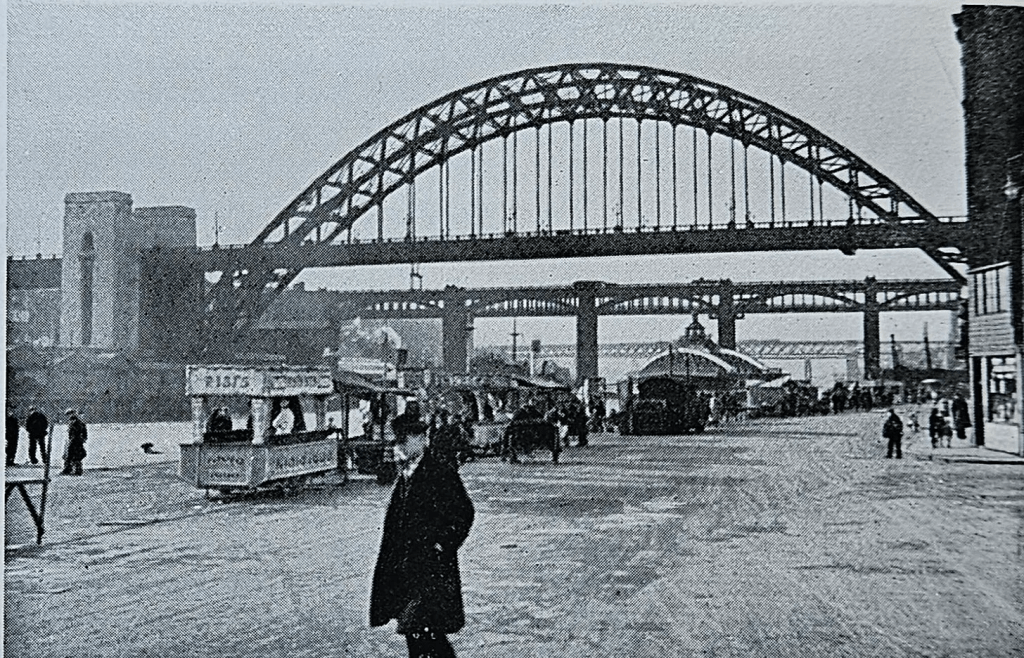

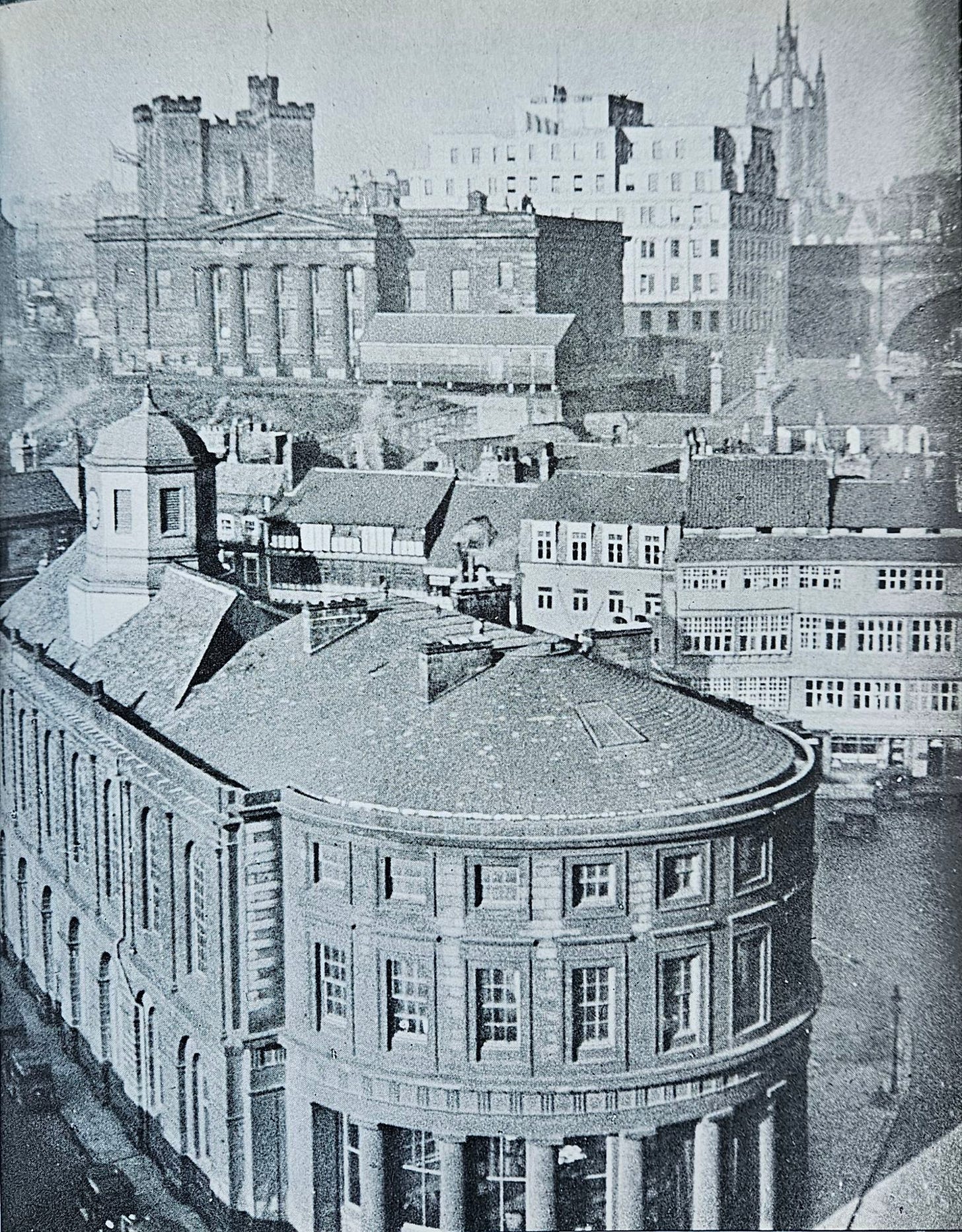

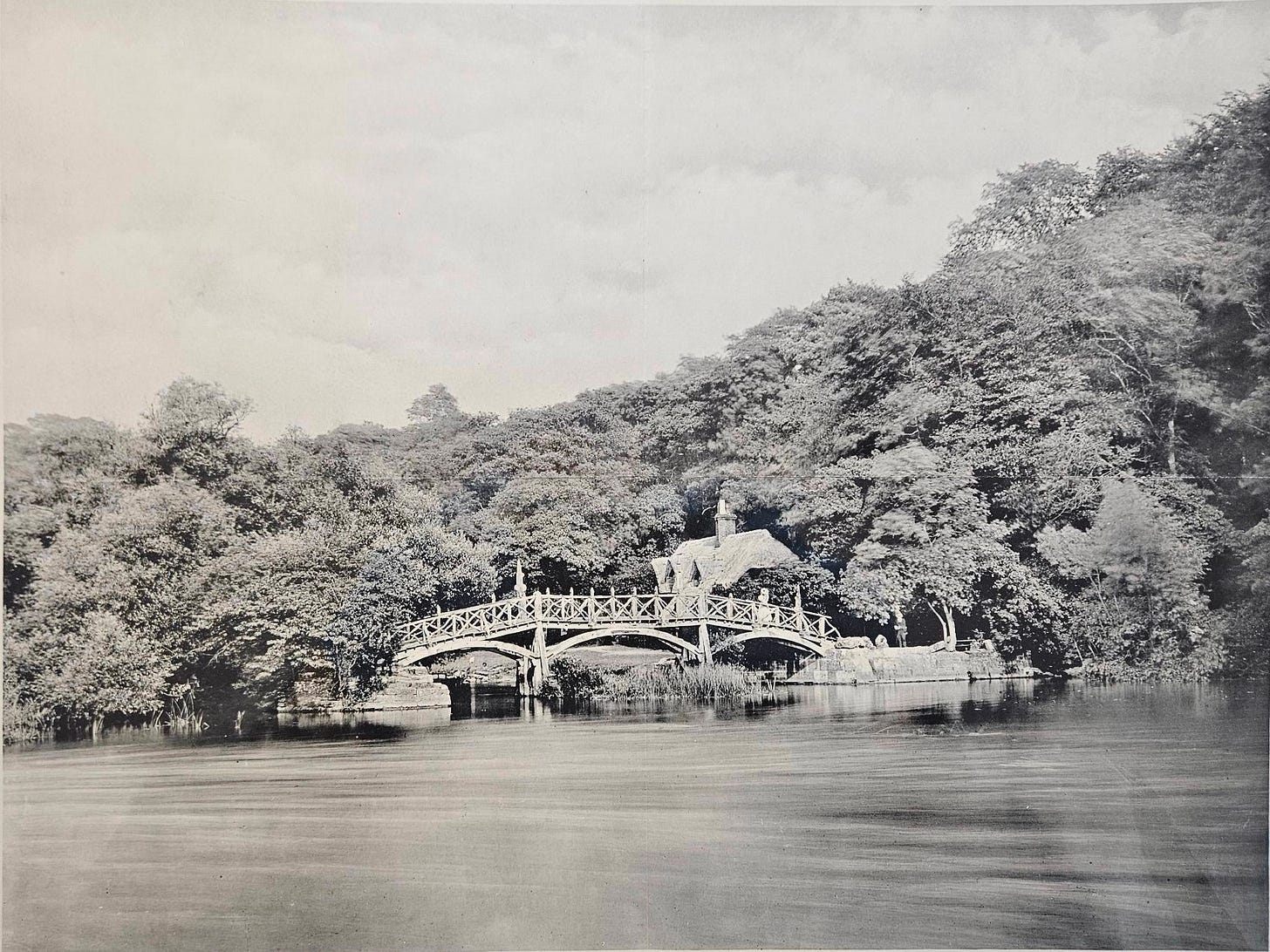

In particular, he was “deeply dissatisfied” with some of the proposed images featuring the historic heart of Newcastle upon Tyne which prior to 1974 was part of Northumberland.

In an effort to resolve what had become an impasse, Sharp wrote to Bruce Allsopp at Oriel Press with a photographic request.

“I am most anxious to obtain, as soon as possible, and to be given permission to reproduce, the following illustrations from Historic Architecture of Newcastle upon Tyne.”

He also took the opportunity to request a copy of the book which he described as “so good I should like to possess it” (THS 42.284).

The following day, Allsopp replied positively enclosing copies of the four glossy prints that Sharp had requested (THS 42.285).

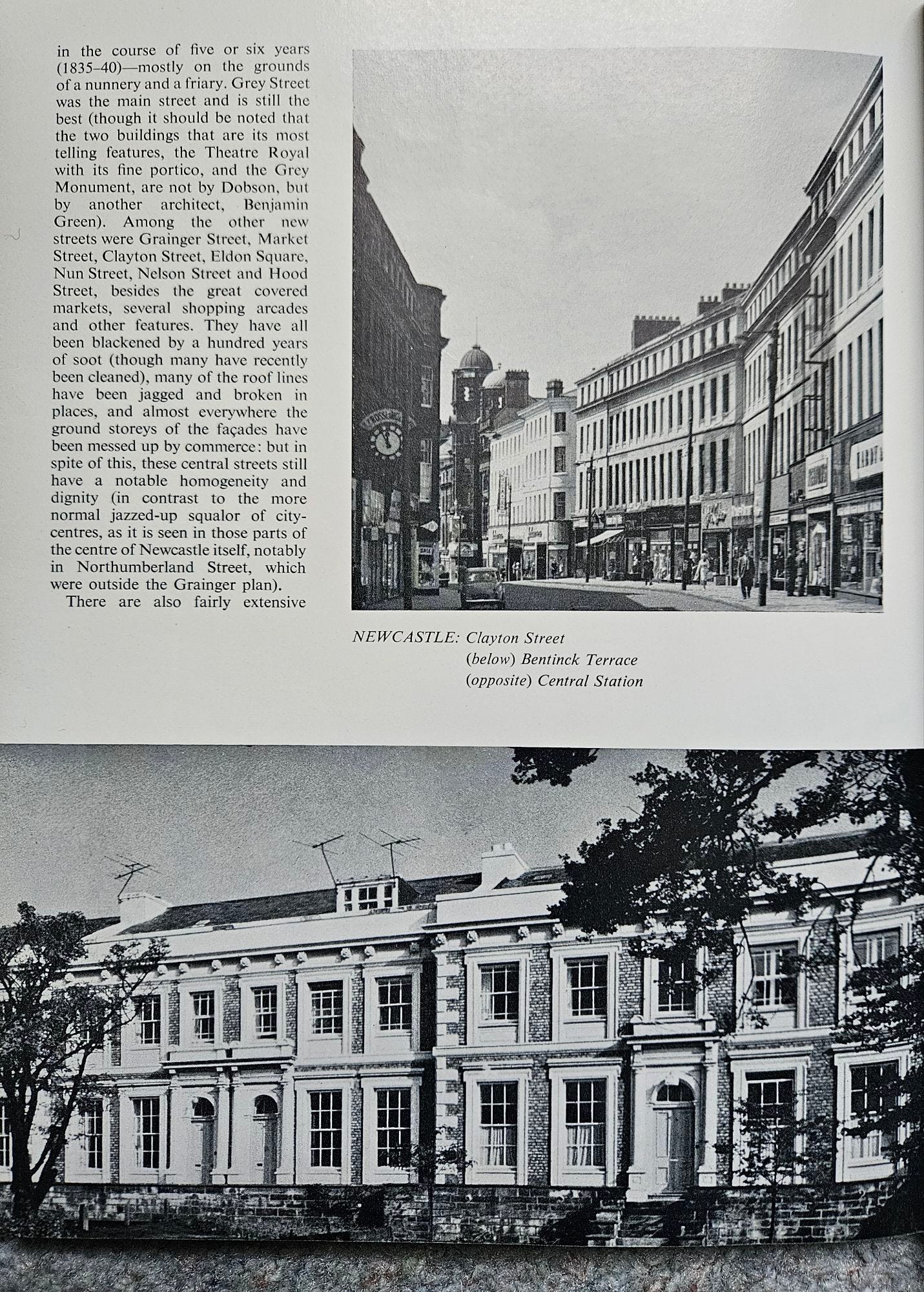

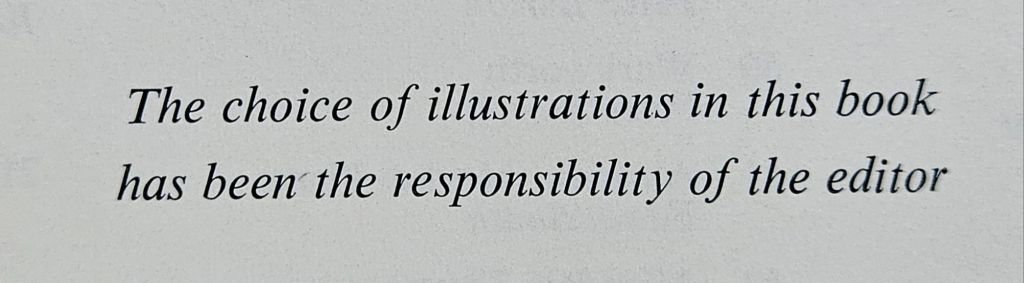

These featured Ursula Clark’s images of (Bessie) Surtees House, Clayton Street, Bentinck Terrace and St. Nicholas Cathedral.

When the book finally appeared, Sharp had succeeded in changing some of the images at the heart of his dispute with Piper including all those obtained from Oriel Press.

Two of Ursula’s shots were given full pages, whilst the other two shared a page with Sharp’s illuminating text.

Sharp had also suggested an acknowledgement for Ursula Clark which duly appeared in his Prefatory Note alongside a mention for ‘Oriel Studios’ suggested by Bruce Allsopp.

However, the disagreement with John Piper as series’ editor surrounding the final choice of photographs for Northumberland: A Shell Guide continued into its publication.

At Sharp’s request, the following text appeared beneath the list of Illustrations.

Leave a comment