The recent release of the first full 3D scan of the wreck of Titanic generated worldwide interest.

The sinking of Titanic is a story that continues to fascinate and one that wove its way into my recently-published doctoral thesis on early press photography.

By 1912, Underwood & Underwood (U&U), the 3D photography company that provided the case study for my thesis, was supplying news photos to newspapers and magazines across the world.

A story I was unaware of before beginning my research was the company’s role in securing a series a Titanic photographs taken by 17 year-old Bernice “Bernie” Palmer using a Kodak Brownie.

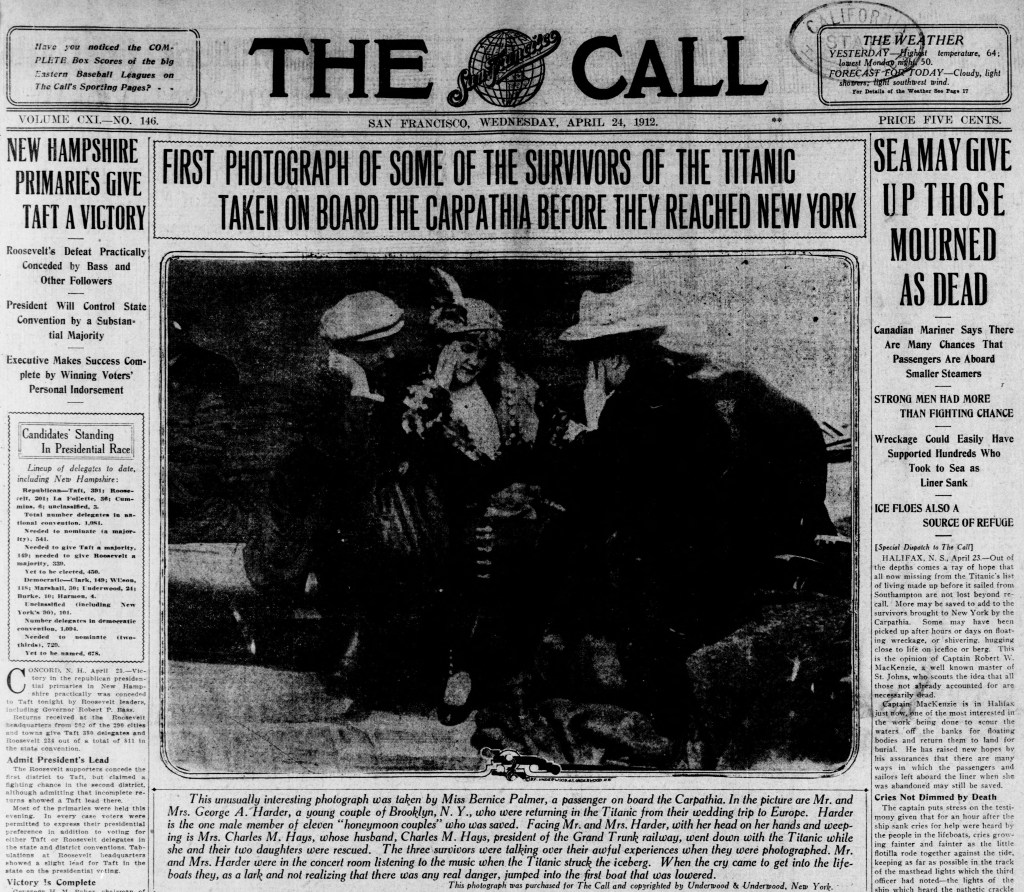

Bernice was a passenger on Carpathia, the ship that rescued passengers from Titanic. She was able to photograph both the iceberg involved as well as survivors recovering on deck in the days following the disaster.

The details are well described and illustrated in a blogpost featuring her remarkable snapshots put together by the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC.

https://www.si.edu/spotlight/titanic-group/bernie-palmer-s-story

According to the National Museum of American History’s account, Bernice was approached on her return to New York by a “newsman” working for Underwood & Underwood who offered to develop, print and return the pictures to her along with $10.

As a result, U&U copyrighted the resulting images and was able to widely distribute her photographs making front-page headlines in the process.

Image provided by University of California, Riverside, CA. Courtesy of Chronicling America.

Note the credit caption at the bottom of the page which states: “This photograph was purchased for The Call and copyrighted by Underwood & Underwood, New York.”

During a research trip to the Smithsonian in 2020, I was fortunate enough to be able to handle and view Underwood & Underwood’s original contractual agreement with Bernice dated 8th February 1913.

As this was several months after the sinking, it is reasonable to assume that by that point, the company had maximised the immediate commercial potential of its “exclusive” photos and and was willing to return the copyright to its owner.

The Epilogue to my thesis explores this sequence of events in more detail and examines some of the questionable behaviour that resulted in pursuit of a journalistic scoop.

If you wish to read more about the role played by stereoscopic 3D photography in shaping press illustration in the decades either side of 1900, you will find a link to the full thesis in my blogpost “Doctoral thesis” (13th May 2023).

Leave a comment